La scala nella roccia

921 gradini che si arrampicano sul fianco del Monte Solaro. La chiamano Fenicia e offre alcuni fra i panorami più belli dell’isola

testo e foto di Alessandro Scoppa

Prima della costruzione della strada tra Capri e Anacapri i due comuni dell’isola erano uniti solo dal “Passetiello”, un erto passo di montagna e da una gradinata che si arrampica a serpentina lungo il ripido fianco del Monte Solaro: la Scala Fenicia.

A dispetto del nome, la Scala non è Fenicia ma Greca. Greca è infatti la tecnica di costruzione, con i gradini scalpellati nella viva roccia; in epoca romana subì un primo restauro, tanto che gli studiosi preferiscono chiamarla scala greco-romana. Con la costruzione della strada, sul finire dell’Ottocento cadde in disuso e rimase inagibile fino al 1998, quando un secondo importante restauro l’ha resa nuovamente percorribile.

Oggi, con i suoi 921 gradini per 1,7 chilometri, copre un dislivello di circa 300 metri ed è uno dei percorsi paesaggistici più interessanti dell’isola. In discesa, da Anacapri si raggiunge Marina Grande in mezz’ora e la Piazzetta di Capri in un un’altra ventina di minuti. Tuttavia, è la salita dal basso a regalare un graduale crescendo di emozioni. Si inizia poco più su del porto di Marina Grande, prendendo la via Fenicia. Oltrepassati i muretti a secco che delimitano antichi vigneti, appaiono i primi gradini. Prima si attraversa una boscaglia abbastanza fitta, poi, a mano a mano che si sale, si scorge sempre più ampio il mare al proprio fianco. Si sale ancora ed ecco che ci si imbatte in una minuscola chiesa, così piccola che sembra una casetta rubata da un presepe: è la cappella di Sant’Antonio da Padova, patrono di Anacapri, sul cui piccolo sagrato ci si può fermare a riprendere fiato: probabilmente questa piazzola di sosta esisteva già in epoca romana, e da qui lo sguardo spazia lungo tutto il golfo di Napoli. Ma il tratto più emozionante è l’ultimo ancora da affrontare. Si passa al di sotto degli imponenti pilastri che reggono la strada e si sbuca al di sopra di essa, inerpicandosi lungo il fianco della montagna che qui cade quasi a piombo. È il tratto dove sono ancora visibili i resti dei gradini greco-romani, ed è anche quello più vertiginoso. Anche aggrappati al parapetto con il batticuore e i sudori freddi, è impossibile restare indifferenti alla vista che si gode da quassù. E finalmente, ecco l’antica avamporta di Anacapri, oltre la quale una volta si doveva attraversare un ponte levatoio, oggi sostituito da una comoda stradina di mattoni rossi. Sollevando lo sguardo, notiamo una strana figura affacciata al parapetto di una villa tutta bianca, su in alto: è la Sfinge di Villa San Michele. Quando negli ultimi decenni dell’Ottocento Axel Munthe arrivò in questo punto, al suo posto c’erano le rovine di una cappella dedicata a San Michele. Scordando in un lampo la fatica della salita, se ne innamorò a prima vista e dopo qualche anno vi costruì la sua dimora che oggi è il famoso museo. E proprio con una rilassante visita ai giardini di Villa San Michele può terminare l’ascesa della Scala Fenicia e iniziare la scoperta di Anacapri.

Certo, per gli antichi anacapresi la Scala Fenicia era tutt’altro che un’idilliaca passeggiata, quanto piuttosto una faticosa scarpinata da dover compiere quotidianamente. Erano soprattutto le donne che, mentre gli uomini erano occupati al lavoro nei campi o imbarcati come pescatori, marinai e calafati, giorno dopo giorno salivano e scendevano le centinaia di gradini portando sul capo acqua, cibo, legna e perfino materiale da costruzione. Se vi foste trovati lungo la Scala Fenicia nel 1719, vi sareste imbattuti in una processione di fanciulle con in testa cassette di legno piene di piastrelle. Sbirciando, avreste notato dipinte su di esse qui una mano, lì una testa di animale, lì ancora un fiore… Erano le 2.500 riggiole del pavimento della Chiesa Monumentale di San Michele, portate lassù in piccoli gruppi da Marina Grande, dov’erano sbarcate una volta cotte nei forni di Napoli.

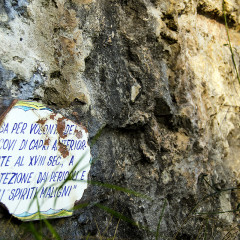

Ma la Scala Fenicia racconta anche altre storie. Durante la salita si notano delle croci incise nella roccia. Furono realizzate per volontà dei vescovi di Capri nel XVII secolo, a protezione dagli “spiriti maligni”, ma anche dalla caduta di massi, eventualità tutt’altro che rara da quelle parti. Nei registri comunali di morte dell’Ottocento, si legge la triste cronaca di una giovanissima ragazza che, colpita da una pietra staccatasi dal monte, si spense nella cappella di Sant’Antonio, dove fu adagiata dalle compagne nel tentativo di fornirle i primi soccorsi. Anni dopo, fu proprio la cappella a essere semidistrutta da una frana; fu poi ricostruita da un anacaprese emigrato con il ricavato di una vincita al lotto. Oggi, oltre alle croci incise, a protezione dalle pietre c’è una robusta rete d’acciaio che imbriglia tutto il versante della montagna.

Al termine della Scala Fenicia, tanti illustri personaggi del passato trovavano ad Anacapri un mondo ideale dove terminare o meglio ricominciare la propria vita. Per gli abitanti del posto invece, c’erano il conforto dei propri cari e il riposo nelle loro case dopo una giornata di fatica. Oggi, lungo i gradini di pietra può capitare di incontrare dei giovanissimi che, zaino in spalla, si cimentano nella salita tornando a casa da scuola; in barba alla moderna strada e agli scooter, questi ragazzi rappresentano un filo rosso con il passato, e sembrano inconsapevolmente ricordarci che per aspera ad astra, attraverso le difficoltà si raggiungono le più alte vette.

The steps in the rock

921 steps climbing up the side of Monte Solaro. They are the Phoenician Steps, and from here you can enjoy some of the best views of the island

text and photos by Alessandro Scoppa

Nine hundred and twenty-one steps climbing up the side of Monte Solaro offering some of the most beautiful views of the island: the Scala Fenicia (Phoenician Steps). Before the road between Capri and Anacapri was built, the two towns were connected only by a steep mountain pass named Passetiello and by the Scala Fenicia’s winding steps along the sheer side of Monte Solaro.

Despite the name, the Steps are not Phoenician but Greek. The construction technique is in truth Greek, with steps chiselled into the rock – scholars in fact prefer to call them the Graeco-Roman steps. A first restoration was carried out in Roman times. When the road across the island was built at the end of the 19th century, the steps were abandoned, neglect made them impassable, a condition that lasted until 1998, when a second major restoration made them accessible once again. Today, the 921 steps cover 1.7 km and a height difference of about 300 metres offering one of the most interesting panoramic itineraries across the island. Descending from Anacapri, Marina Grande can be reached in half an hour and La Piazzetta di Capri can be reached in fifty minutes. It is, however, the climb upwards that rewards you with a crescendo of emotions. It begins a little above the Marina Grande port along via Fenicia. After passing the dry stone walls that mark the boundaries of ancient vineyards, the first steps appear. First you cross rather thick woods, then, as you go higher, you have a more extensive view of the sea. Climbing higher still you come to a tiny church, so small it seems like a little house stolen from a nativity scene: it is the chapel of Saint Anthony of Padua, patron saint of Anacapri. You can stop in the churchyard and catch your breath: probably this stopping place already existed in Roman times, and from here the whole length of the Bay of Naples can be seen. The most thrilling stretch, however, is the last to be tackled. You pass under some impressive pillars that support the road and you find yourself above the road itself, clambering up the side of the almost sheer mountain side. This stretch is where the remains of the Graeco-Roman steps can still be seen, and it is also the most dizzying. Even when gripping the railings, with your pulse racing and breaking out in a cold sweat, it is impossible not to enjoy the view from up here. And here at last are the stone gates of Anacapri, where once, after passing through, there was a drawbridge to cross which has now been substituted with an easy red brick road. Looking up, you notice a strange figure on the parapet of a white villa, high up: it is the sphynx, and the villa is Villa San Michele. In the last decades of the 18th century when Axel Munthe arrived here, there were only the ruins of a chapel dedicated to Saint Michael. For Munthe it was love at first sight, immediately forgetting the effort of the climb, and after a few years, he built his home here which today is a famous museum. And it is with a relaxing visit to the Villa San Michele gardens that the climb up the Phoenician Steps ends and the exploration of Anacapri begins.

For the ancient inhabitants of Anacapri it was certainly not so much an idyllic stroll as a very hard trek that had to be made every day. It was mainly the women who day after day climbed up and down the hundreds of steps carrying water, food, wood and even building material on their heads while the men were busy working in the fields or on boats as fishermen, seamen and caulkers. If you had found yourself on the Phoenician Steps in 1719 you would have bumped into a procession of young girls carrying wooden boxes full of tiles on their heads. If you had taken a peek, you would have seen here a hand, there an animal head, there a flower painted on the tiles. They were the 2,500 riggiole (Neapolitan majolica tiles) for the flooring of the Monumental Church of San Michele, carried up there in small groups from Marina Grande, where they had been unloaded after having been fired in the Naples ovens.

But Phoenician Steps also tell other stories. Crosses carved in the rock can be seen on the climb up. It was the wish of the bishops of Capri in the 17th century to have them carved as protection against “evil spirits”, and also against the falling rocks, a far from rare occurrence in those parts. In the 19th century municipal death registers, there is the sad story of a young girl hit by a falling rock. She died in the chapel of Saint Anthony where she had been taken by her friends who tried to save her. Years later, it was precisely the chapel that was partly destroyed by a landslide; it was then rebuilt by an Anacaprese emigrant and paid for with his lottery win. Today, apart from the carved crosses, there is a sturdy steel net that keeps the whole side of the mountain in check.

At the end of the Phoenician Steps, many illustrious celebrities of the past found in Anacapri an ideal world where they could live out their lives or better still make a fresh start. The inhabitants, on the other hand, found the comfort of their loved ones and rest in their houses after a hard day’s work. Today, along the stone steps, you meet youngsters with schoolbags on their backs facing the climb on their way home from school; in spite of a modern road and scooters, these kids represent a common thread with the past, and seem to unknowingly remind us that, as the Latins put it, per aspera ad astra, a rough road leads to the stars.

Dedicata a Sant’Antonio

La cappella di Sant’Antonio è detta anche cappella dei marinai perché in passato il fuoco che vi ardeva all’interno fungeva da guida e conforto a chi andava per mare di notte. Fu edificata tra il XVII e il XVIII secolo su una piazzola naturale a metà della Scala Fenicia, considerata posizione strategica non solo per la sosta. Durante l’occupazione francese seguita alla presa di Capri nel 1808, fu fortificata con un muro di difesa lungo l’intero sagrato. Tenuta nei secoli sempre in efficiente stato dal semplice amore degli anacapresi per il loro Santo, sulla facciata la lapide marmorea ricorda il benefattore che restaurò la cappella con il ricavato di una vincita al lotto. Sant’Antonio in persona gli aveva dato i numeri in sogno!

La cappella di Sant’Antonio è detta anche cappella dei marinai perché in passato il fuoco che vi ardeva all’interno fungeva da guida e conforto a chi andava per mare di notte. Fu edificata tra il XVII e il XVIII secolo su una piazzola naturale a metà della Scala Fenicia, considerata posizione strategica non solo per la sosta. Durante l’occupazione francese seguita alla presa di Capri nel 1808, fu fortificata con un muro di difesa lungo l’intero sagrato. Tenuta nei secoli sempre in efficiente stato dal semplice amore degli anacapresi per il loro Santo, sulla facciata la lapide marmorea ricorda il benefattore che restaurò la cappella con il ricavato di una vincita al lotto. Sant’Antonio in persona gli aveva dato i numeri in sogno!

Ogni anno, nei primi tredici giorni di giugno si rinnova l’annuale tredicina di Sant’Antonio: di primo mattino vi si celebra la messa al termine della quale si distribuisce il pane benedetto. Le celebrazioni si ripetono poi nella chiesa parrocchiale di Santa Sofia, in posizione e orario più comodi; ma è bello vedere quante persone ancora oggi riempiono la piccola chiesa e l’ancor più piccolo sagrato, mantenendo viva una tradizione di fede e devozione. | The Chapel of Saint Anthony. The chapel of Saint Anthony is also known as the seamen’s chapel because in the past the fire that used to burn inside the chapel was a guide and a comfort to those who were at sea during the night. It was built between the 17th and 18th centur on a natural ledge, half way up the Phoenician Steps and was considered not only a resting place but also a strategic position. Capri was taken by the French in 1808, and during the French occupation the chapel was fortified with a defence wall all along the churchyard. Through the centuries, this chapel has been cared for and kept in an efficient state by the devout Anacapri inhabitants. On the facade, the marble plaque commemorates the benefactor who restored the chapel with his lottery win. It was Saint Anthony himself who gave him the winning numbers in a dream! Every year, during the first thirteen days of June the annual tredicina di Sant’Antonio, the thirteen-day novena to Saint Anthony is renewed: mass is celebrated early in the morning and at the end of mass blessed bread is distributed. The celebrations are repeated in the parish Church of Saint Sofia, a more convenient location and at a more convenient time; it is wonderful to see how many people still fill the small Church and the even smaller churchyard today, keeping alive a tradition of faith and devotion.

Una sosta Doc

Un’antica, minuscola cantina ricavata dalle storiche cisterne romane e che dalla Scala Fenicia prende il nome. Qui nasce il Capri Doc bianco frutto del raccolto della piccola vigna che si estende per circa 4.000 metri quadrati su antiche terrazze contenute da muri a secco. Una raccolta esclusivamente manuale. Forbici alla mano ci si arrampica sui pergolati e si riempiono le cassette che poi vengono trasportate a spalla in cantina.

Un’antica, minuscola cantina ricavata dalle storiche cisterne romane e che dalla Scala Fenicia prende il nome. Qui nasce il Capri Doc bianco frutto del raccolto della piccola vigna che si estende per circa 4.000 metri quadrati su antiche terrazze contenute da muri a secco. Una raccolta esclusivamente manuale. Forbici alla mano ci si arrampica sui pergolati e si riempiono le cassette che poi vengono trasportate a spalla in cantina.

Per quanti volessero conoscerla più da vicino è possibile richiedere una visita guidata al terreno e alla cantina. Troverete un bianco elegante, sapido, con leggere note agrumate ottimo motivo per una visita con degustazione. | Stop for a glass. A tiny, ancient wine cellar located in what once were Roman cisterns, taking its name from the Phoenician Steps: this is where White Capri Doc (controlled designation of origin) wine is born from the exclusively hand-picked grapes of the small vineyard covering about 4,ooo square metres of ancient terraces framed by dry stone walls. With shears in their hands, the pickers climb onto the pergola vines and fill crates that are then carried down to the wine cellar by hand. For those who would like to learn more and at close quarters, guided visits to the vineyards and wine cellars can be requested. Here you will be greeted with a glass of Capri’s elegant, sapid wine with light citrusy notes: an excellent reason for a visit with wine tasting.

Info: info@scalafenicia.com • tel. 081.8389403