Ritrovarsi in Paradiso

Ritrovarsi in Paradiso

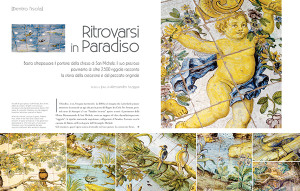

Basta oltrepassare il portone della chiesa di San Michele. Il suo prezioso pavimento di oltre 2.500 riggiole racconta la storia della creazione e del peccato originale

testo e foto di Alessandro Scoppa

Il Paradiso, si sa, bisogna meritarselo. La Bibbia ci insegna che è più facile passare attraverso la cruna di un ago che per la porta del Regno dei Cieli. Per fortuna, però, nel cuore di Anacapri c’è un “Paradiso in terra” aperto a tutti: il pavimento della Chiesa Monumentale di San Michele, ossia un tappeto di oltre duemilacinquecento “riggiole”, le tipiche mattonelle napoletane, raffiguranti il Paradiso Terrestre con la cacciata di Adamo ed Eva da parte dell’Arcangelo Michele.

Gli stranieri, quest’opera unica al mondo nel suo genere la conoscono bene; anche prima di arrivare a Capri per la prima volta. Perfino in pieno inverno, quando tutto sull’isola è fermo e, a parte le escursioni panoramiche splendide in ogni stagione, nessun’altra attrazione è disponibile, gruppetti di turisti o viaggiatori solitari salgono ad Anacapri e puntano diritti alla chiesa di San Michele. Li immaginiamo nelle loro case, o seduti in qualche caffè, che preparano il viaggio, e guardano in rete le foto del pavimento, ne leggono le copiose testimonianze e comprendono come una visita ad Anacapri non possa prescindere da almeno una capatina alla chiesa. Alcuni, dunque, dedicheranno al pavimento di San Michele un fugace giro lungo le passerelle di legno che evitano il calpestio sulle delicate riggiole, un “must to do” sull’isola. Altri, invece, si soffermeranno ai bordi di quell’arazzo di maiolica più a lungo, scrutandolo alla ricerca dei tantissimi dettagli, per raggiungere il massimo dello stupore quando, dietro la solerte guida di Elena, Maria e Titti, che si alternano alla custodia della chiesa-museo, saliranno la scala a chiocciola e dall’alto della cantoria potranno ammirare l’opera nel suo spettacolare insieme.

Chi invece è raro incontrare nella chiesa, sono i capresi. Forse perché vivendo su un’isola paradisiaca, pensano che il Paradiso (di San Michele) può attendere…

Eppure, l’opera fu creata proprio per loro. Quando nel 1719 si completano i lavori per il restauro della chiesa e dell’annesso monastero femminile, a Leonardo Chiaiese, maestro maiolicaro abruzzese che probabilmente si basò su disegni dello scultore Giuseppe Sanmartino, fu commissionato ciò che doveva offrire alle monache un mezzo per alleviare il peso della clausura: dall’alto dei coretti, al riparo delle grate lignee che ancora oggi è possibile vedere attorno alla navata, gli sguardi delle religiose correvano stupefatti per quell’immensa finestra sul mondo esterno, compiendo con l’immaginazione un viaggio che non potevano fare fisicamente. Ma, soprattutto, l’opera doveva avere un chiaro significato allegorico, rivolto all’intera comunità isolana: in accordo con i dettami della Controriforma, secondo cui l’arte nelle chiese doveva educare anche tramite la magnificenza e lo stupore che ne derivava, il pavimento di San Michele fu pensato come un’immensa storia illustrata della creazione e del peccato originale. Non a caso gli animali più vicini alla realtà dei contadini di allora, il bue, la mucca, il toro, sono posti all’ingresso, perché più comuni, immediatamente riconoscibili; entrando nella casa di Dio, il caprese si sarebbe sentito subito a casa propria. In questo gruppo risalta una capra ritta su una roccia in mezzo al fiume, lo “scoglio”, chiaro riferimento all’isola di Capri e alla più immediata etimologia del suo nome. Da quel punto, agli occhi si sarebbe offerta una varietà impressionante di animali, ognuno raffigurante “non soltanto i vizi umani, ma gli stessi insegnamenti morali o spirituali della dottrina cristiana”, come si legge in una teca affissa in chiesa che elenca il simbolismo relativo a ciascuna creatura. Tra esse due scimmiette, una che tiene un topolino per la coda, l’altra che porge un frutto a un orso, danno origine a scene di particolare bellezza. Al centro della composizione, l’Arcangelo Michele con la spada infuocata e l’indice teso scaccia Adamo in precipitosa fuga ed Eva che si volta supplichevole in un estremo quanto vano tentativo di conciliazione. In alto, vero punto focale dell’intera scena, troneggia l’Albero della Vita, sotto un cielo che sfuma dal giorno alla notte stellata.

Il pavimento del Paradiso costò alle monache “solo” 200 ducati, circa quanto un’odierna utilitaria, poiché opere di quel genere erano ritenute estremamente delicate e di breve durata. Eppure, dopo quasi trecento anni, è ancora in ottima salute, e continua a ottenere pienamente lo scopo per cui fu concepito: sorprendere e insegnare.

Custode prezioso

La Congrega dell’Immacolata Concezione, operante a Capri dal 1685, ottenne l’affidamento della chiesa di San Michele nel 1817 da re Ferdinando I delle Due Sicilie. Ma, pur essendo la cura della chiesa e del prezioso pavimento del Paradiso Terrestre la sua attività principale, la Congrega organizza anche altre iniziative religiose e culturali di rilievo. Tra queste, un posto importante spetta alla Novena dell’Immacolata, tra novembre e dicembre. In quell’occasione, il pavimento è coperto da un ampio tappeto per proteggerlo dal calpestio dei fedeli; ma la visita alla chiesa, tuttora consacrata, resta un piacere per credenti e non, magari per ammirare meglio anche le altre opere d’arte che custodisce, come i dipinti e gli altari lignei del Settecento, o l’altare maggiore in marmo e pietre preziose; ma anche chiudendo gli occhi e lasciandosi trasportare dalle note delle antiche litanie mariane diffuse dall’organo settecentesco, un patrimonio culturale in musica che altrimenti rischierebbe l’oblio. | Precious guardian. In 1817, the church of San Michele was entrusted to the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception, which has been operating on Capri since 1685, by King Ferdinando I of the Two Sicilies. But although its principal activity is to look after the church with its precious floor of Earthly Paradise, the Confraternity also organizes other important religious and cultural initiatives. One of the most important is the Novena of the Blessed Virgin, between November and December. On this occasion, the floor is covered with a large carpet to protect it from the feet of the worshippers; but the visit to the church, which is still consecrated, remains a pleasure for believers and unbelievers alike, perhaps to have more chance to admire the other works of art that it contains, such as the 18th century paintings and wooden altars, or the high altar in marble and precious stones; but also to be able to close their eyes and allow themselves to be transported by the music of the ancient Marian liturgies played on the 18th century organ, a cultural heritage of music that would otherwise risk oblivion.

Finding yourself in Paradise

You just need to walk through the door of the church of San Michele. Its fine floor with over 2,500 “riggiole” tells the story of Creation and original sin

text and photos by Alessandro Scoppa

As we all know, you need to earn your place in Paradise. The Bible teaches us that it is easier to pass through the eye of a needle than to enter the gates of the Kingdom of Heaven. Fortunately, however, there is an “Earthly paradise” in the heart of Anacapri that is open to everyone: the floor of the Chiesa Monumentale di San Michele, a “carpet” of over two thousand five hundred “riggiole”, the typical Neapolitan ceramic tiles, depicting the Earthly Paradise and the expulsion of Adam and Eve by the Archangel Michael.

Foreigners know about this work, the only one of its kind in the world, even before they come to Capri for the first time. Even in mid winter, when the island shuts down and, apart from the panoramic trips that are splendid in all the seasons, no other attraction is available, groups of tourists or independent travellers climb up to Anacapri and head for the church of San Michele. We can imagine them at home or sitting in a café, preparing for their trip as they look at the photos of the floor on the internet, read the many descriptions and realize that a trip to Anacapri simply has to include at least a brief visit to the church. So some of them will devote a quick trip to the floor of San Michele as one of the island’s “must do’s”, walking on the wooden walkways to avoid treading on the delicate tiles. Others will linger at the edge of that majolica tapestry for longer, examining it to explore all its wealth of detail; their amazement reaches a peak when, under the diligent guidance of Elena, Maria and Titti, who take turns as custodians for the church-museum, they go up the spiral staircase to the choir loft and gaze on the work from above, seeing it in all its spectacular entirety.

But it’s a rare occurrence to meet any Capri inhabitants in the church. Perhaps because, since they are living in an island paradise, they think that Paradise (the one in San Michele) can wait… And yet the work was created specifically for them. When the restoration works on the church and the attached convent were completed in 1719, Leonardo Chiaiese, a Majolica master craftsman from Abruzzo, was commissioned to create this work that would give the nuns something to alleviate the burden of their vows of seclusion, probably basing it on designs by sculptor Giuseppe Sanmartino. From the nuns’ choir lofts above, screened by the wooden grilles that can still be seen today around the nave, the nuns would have gazed in amazement at that immense window onto the world, embarking on a journey in their imagination that they could not make in reality. But above all, the work had to have a clear allegorical meaning, aimed at the whole island community: in accordance with the dictates of the Counter Reformation, which ruled that art in churches should educate, including through its magnificence and the amazement this engendered, the floor of San Michele was conceived as an immense illustrated history of the Creation and of original sin. It’s no coincidence that the animals that were closest to the peasants’ lives at the time, the ox, the cow, the bull, are near the entrance, because they were the most common and immediately recognizable; as they entered the house of God, the people of Capri would immediately feel at home. Standing out from this group is a nanny goat, standing erect on a rock in the middle of a river, with the “rock”, being a clear reference to the island of Capri and to the most immediate etymology of its name (from capra, or she-goat). Following on from that point, their eyes would have taken in an impressive range of animals, each depicting “not only the human vices, but the moral or spiritual teachings of Christian doctrine”, as is written inside a display case in the church that lists the symbolism with regard to each animal.

There are two particularly lovely scenes featuring monkeys, one holding a mouse by the tail, the other offering a fruit to a bear. At the centre of the work, stands the Archangel Michael with his flaming sword and his outstretched finger, expelling Adam, in headlong flight, and Eve who is turning beseechingly, in a last, vain attempt at conciliation. At the top is the Tree of Life, the true focal point of the whole scene, beneath a sky gradating from daytime into starry night.

The floor of Paradise cost the nuns “just” 200 ducats, about the cost of a small car today, since works of this kind were considered extremely delicate and of short duration. Yet, almost three hundred years later, it is still in excellent condition and continues to fully achieve the purpose for which it was designed: to astonish and to teach.

Torna a sommario di Capri review | 35