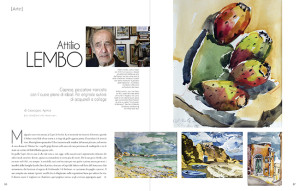

Attilio Lembo

Caprese, pescatore mancato con il cuore pieno di ideali. Poi originale autore di acquerelli e collage

di Giuseppe Aprea | foto di Raffaele Lello Mastroianni

Malgrado tutto vive ancora, la Capri di Attilio. La si intravede nei mattini d’inverno, quando il Solaro tiene fede al suo nome e si tinge di giallo appena prima d’incendiarsi di arancio vivo. Meraviglioso spettacolo. O la si incontra sulle stradine del monte più caro, nel sorriso di una donna di Tiberio: ha i capelli grigi fermati sulla nuca da una pettinessa di madreperla e tra le mani un cestino di fichi d’India appena colti.

In quella Capri che era sua (e che tale resta a noi, oggi, nella sua pittura) i soprannomi volavano alti sulla vita di uomini e donne, spesso raccontandone la storia più dei nomi. Per la sua gente Attilio, che era nato nel 1931, era sempre ’a sorechella, così com’era stato per suo padre e prima ancora per tutti i membri della famiglia Lembo fino al primo, sbarcato a Capri dal Salento sul finire del Settecento. Era nientemeno che battitore al seguito di Ferdinando I di Borbone, re cacciatore di quaglie e pernici. Il suo compito era stanare i poveri uccelli che si rifugiavano nella vegetazione bassa per salvarsi la vita.

E doveva essere il migliore tra i battitori, quel pugliese antico, se gli avevano appioppato quel nomignolo, che nella realtà apparteneva al più veloce e più scaltro tra i topi di campagna. In ogni caso ’a sorechella nell’isola decise di fermarsi per sempre, sposò la figlia di un pescatore e disse addio alle corse a perdifiato tra i cespugli di mirto e di lentisco.

Di tutta questa furbizia di famiglia, Attilio Lembo, uomo del Novecento ma anche dell’Ottocento, con il cuore ricolmo di ideali e i piedi sospesi tra il cielo e la terra, non ne aveva ereditato neanche un po’. Neppure la velocità gli si addiceva, in verità, semmai più consono gli era il suo contrario, la lentezza. Ma la vita, come si sa, non sempre consente all’uomo di sceglierne il ritmo e i contenuti, e fu solo per il grande rispetto di quelle rigide regole che nel suo tempo ancora scandivano i rapporti nelle famiglie, che accettò di fare il mestiere di pescatore cui fu ad un certo punto chiamato dal padre insieme ai fratelli. Così, il mare della Marina Piccola di Capri fu per qualche anno tutto il suo mondo. Non fu facile resistere.

Per amore ma anche per odio, dunque, il mare e le marine divennero familiari ai suoi occhi di giovane artista. Nei primi anni i suoi erano solo disegni a matita, eseguiti o soltanto rifiniti nella quiete della minuscola dimora di via Sopramonte, in cui era andato a vivere con la sorella ed i genitori ormai vecchi. Poi, pian piano, sempre timidamente com’era nella sua indole, ecco apparire sul foglio il colore, per lo più quello prediletto dell’acquerello. Con poche pennellate prendevano forma gli amati melograni, le fette di cocomero, i dolci fichi che le donne mettevano a seccare al sole, sui tetti.

Sopravvissuto alle fatiche del mestiere di mare, Attilio era nel frattempo approdato a più tranquilla e terrestre occupazione e partecipato (con timore pari all’entusiasmo) alla prima mostra della sua vita, una collettiva promossa dallo scrittore Edwin Cerio e ospitata nel suo prestigioso Centro Caprense. Anno per lui particolarmente fortunato, quel 1951 era proseguito con la sua prima uscita dall’isola, coincisa con il servizio militare e, grazie a quello, sfociata infine in un lungo soggiorno romano. Nei musei della città aveva conosciuto i pittori dell’Ottocento e del Novecento italiano, ma anche Picasso, Klee e le avanguardie. Tanta bellezza lo aveva inebriato al punto che se n’era tornato a Capri con la cartella dei disegni semivuota, per aver speso tutto il suo tempo a studiare i grandi del passato. Ma anche con l’animo leggero dell’uomo che guarda finalmente in faccia il suo destino. A dire il vero portava con sé anche una nuova passione, che sentiva forse pari a quella per l’arte: era quella per la politica. Amava definirsi un socialista post-risorgimentale e si può dire con certezza che in fondo in fondo, anche dopo averne scoperto i lati meno luminosi, restò per sempre fedele a quel magnifico ideale.

Poi un giorno conobbe la dolce Palmina e se ne innamorò. Lei discendeva da quegli albanesi che, fuggiti dal loro paese invaso dai Turchi, nel XV secolo, avevano formato una comunità nelle zone tutt’intorno a Cosenza. Insieme a lei viaggiò attraverso quelle terre, scoprendo con commozione la povertà dignitosa in cui viveva quella gente, fiera delle sue origini e rispettosa delle tradizioni dei padri. Di ritorno da quella Calabria per dare principio alla sua vita di uomo di famiglia, questa volta la cartella da disegno di Attilio era traboccante di schizzi: paesaggi di montagna, aspri e nello stesso tempo dolci allo sguardo, ulivi centenari dal corpo tormentato e castagni maestosi, e poi bellissimi volti femminili. Inutile dire quanto la voglia di trasformare quegli appunti di viaggio in quadri che ne esaltassero le forme e le sfumature di colore divenne subito fortissima e tutta quell’ansia creativa, alla fine, partorì l’idea di un nuovo cammino artistico. Non con l’acquerello né con i colori ad olio avrebbe ricreato il vero, bensì con la carta e la colla. Un collage, ecco. Detto fatto. Con l’entusiasmo della prima volta gli fu lieve e anzi piacevole il lungo lavoro iniziale, lo stesso che avrebbe continuato a ripetere per tutto il resto della sua vita. Dapprima sceglieva la carta tra quelle che colpivano di più la sua immaginazione: l’interno rosa o azzurro delle buste da lettera, le pagine del glorioso Avanti dei suoi anni, i fogli patinati di una rivista di moda, persino una carta abrasiva. Poi, con il pennello e tanto sentimento, dava a quella carta stanca un colore ed una nuova vita, che non ne cancellasse però del tutto la precedente. Infine ritagliati nelle dimensioni più adatte al soggetto, preparava i robusti cartoni destinati ad ospitare la composizione.

Al termine di quel lavoro duro ed entusiasmante poteva aver inizio la vera e propria composizione. Lentamente, tra mille ripensamenti e qualche insofferenza, il collage prendeva forma, sospeso tra le sue mani e i suoi pensieri: centinaia di frammenti di colori diversi si componevano come per incanto in immagini. Per quelle – le case della Marina Grande, il faro di Punta Carena, la chiesetta di Sant’Anna – nessun disegno preparatorio era stato necessario. E avveniva così che l’opera finita, parto della memoria e segno dell’affetto per le cose, affascinasse per l’immediatezza e la spontaneità. Una sorta di candore infantile.

Pur continuando a cimentarsi in altre tecniche, il collage divenne il luogo dell’incontro amoroso di Attilio Lembo con Capri. Anche, e forse soprattutto, dopo che una serie di circostanze lo costrinsero ad un certo punto ad abbandonare l’isola della sua vita e a prendere casa a Napoli. Fu un distacco drammatico, in un certo senso simile alla separazione di un figlio dalla madre. C’era un unico modo, per l’artista e per l’uomo, per rendere meno struggente la nostalgia: era darle forma d’arte, ricomponendo con i frammenti di carta colorata le immagini più care, i luoghi amati, i momenti di felicità o di sofferenza. Ed è quel che Attilio fece, in ognuno dei giorni che visse, fino a sette anni fa.

Oggi gli amici non lo incontrano più per le strade dell’isola, eppure continuano a vederlo. È da qualche parte nel mondo, con gli occhi quasi spenti e le mani che tremano. Alla luce di una lampada ritaglia carta di giornale cui darà una mano di colore grigio chiaro, per un collage il cui soggetto ama ripetere spesso, ora che è lontano. È la sua piccola camera nella casetta di Sopramonte, con il soffitto un po’ sgretolato e una sedia sola. La finestra è chiusa, l’unica gruccia nell’armadio è vuota e il letto sfatto.

Come dopo che l’ospite è partito.

Attilio lembo

Native Caprese and failed fisherman, with a heart brimful of ideals. And later, an original artist creating watercolours and collages

by Giuseppe Aprea | photos by Raffaele Lello Mastroianni

Despite everything, Attilio Lembo’s Capri is still living. You can catch a glimpse of it on winter mornings, when Monte Solaro stays true to its name and becomes tinged with yellow just before it bursts into bright orange flame: a wonderful spectacle. Or you may meet it on the paths of his favourite mountain, in the smile of a woman in Tiberio: she has grey hair tied at the nape of her neck with a hair comb made of mother of pearl, and she’s holding a basket of freshly picked prickly pears. In Attilio’s Capri (that remains to us today in his paintings), nicknames played a key part in the lives of the men and women, often telling a story rather than just being names. Attilio, who was born in 1931, was always known to his own people as ‘a sorechella (the little rat), like his father before him and all the members of the Lembo family right back to the first one who landed on Capri from Salento, at the end of the 18th century. He was none other than the beater for Ferdinand I of Bourbon, the regal hunter of quail and partridge. His task was to flush out the poor birds that had taken refuge in the undergrowth to save their lives. And he must have been the best of the beaters, that ancestor from Apulia, to have been given that nickname, since it actually refers to the fastest and most cunning of all the countryside rats. In any case, the little rat decided to stay there for ever: he married a fisherman’s daughter and bade farewell to the breakneck races through myrtle and lentisk bushes. But Attilio Lembo, a man of the 20th century but also the 19th, with a heart brimful of ideals and his feet suspended somewhere between heaven and earth, didn’t inherit even the tiniest bit of the family cunning. Nor its speed, either; if anything, it was quite the opposite and he found that a slow pace suited him. But as we know, life doesn’t always allow us to choose our own rhythm and tenor of life, and it was only out of his great respect for the rigid rules that still governed family relationships at that time, that he agreed to become a fisherman when called on to do so by his father, together with his brothers. So for some years the sea of Marina Piccola on Capri was his entire world. It wasn’t easy to resist. It was with feelings of both love and hate, then, that the sea and harbours became familiar to the eyes of the young artist. In the early years he only did pencil sketches, executed or simply refined in the peace of the tiny house in Via Sopramonte, where he had moved with his sister and now elderly parents. Then, bit by bit, still timidly as was his nature, colour appeared on the paper, mainly the colours suited to watercolours. With a few brushstrokes, his beloved pomegranates took shape, along with slices of water melon and the sweet figs that the women would spread out on the roofs to dry in the sun. Meanwhile, having survived the toils of a seafaring life, Attilio had managed to obtain a more peaceful, terrestrial occupation, and he took part (shyly but enthusiastically) in the first exhibition of his life, a collective exhibition staged by writer Edwin Cerio and hosted in his prestigious Centro Caprense. That year, 1951, was an especially fortunate year for Attilio, as it was also the year when he first left the island, to do his military service, which led to a long stay in Rome. There in the city’s museums he became acquainted with the Italian artists of the 19th and 20th centuries, but also with Picasso, Klee and the avant-garde. He became so intoxicated with all that beauty that he returned to Capri with his folder of drawings half-empty, having spent all his time studying the great masters of the past, but also with the lighter heart of someone who is finally looking his destiny in the eye. In fact, he brought back a new passion with him, one for which he felt as strongly as for his art: politics. He liked to call himself a post-Risorgimento Socialist, and it is certainly true that in the end, even after having discovered its less appealing side, he always remained loyal to that magnificent ideal. Then one day he met the sweet Palmina and he fell in love. She was a descendant of the Albanians who had fled their country after it was invaded by the Turks in the 15th century, and had formed a community in the area around Cosenza. Together Attilio and Palmina travelled through the area, moved by the dignified poverty in which the people lived, with pride in their origins and respect for the traditions of their forefathers. This time, on his return from Calabria to begin life as a family man, Attilio’s drawing folder was overflowing with sketches: mountain landscapes, harsh yet at the same time gentle to look at, centuries-old olive trees with twisted trunks, majestic chestnut trees, and beautiful female faces. Needless to say, his desire to transform those travel sketches into paintings that would enhance their forms and shades of colour immediately grew very strong and in the end, all that creative anxiety gave birth to an idea for a new artistic path. It was not with watercolours, nor oil paints that he would create truth, but with paper and glue: a collage, in other words. No sooner said than done. With a first timer’s enthusiasm, the initial long labour entailed was light and enjoyable, and he continued making collages for the rest of his life. At first he chose the paper that most captured his imagination: the pink or blue insides of envelopes, the pages of the glorious Avanti newspaper of the time, the glossy pages of a fashion magazine, even abrasive paper. Then, with his brush and plenty of feeling, he gave that tired paper colour and a new life, though one that didn’t completely cancel out all its former life. Finally, he prepared the strong cardboard that would house the composition, cut to the most appropriate size for the subject. At the end of that difficult, exciting labour, the real process of composition could begin. Slowly, rethinking a thousand times and with some impatience, the collage would take shape, suspended between his hands and his thoughts: hundreds of fragments of different colours would come together into images, as though by magic. No preparatory design was necessary for these – the houses at Marina Grande, the lighthouse at Punta Carena, the little church of Sant’Anna. And so it was that the finished work, the fruit of memories and a sign of his affection for these things, fascinated with its immediacy and spontaneity, with a sort of childlike innocence. Although he continued to try out other techniques, collages became the setting for Attilio Lembo’s love affair with Capri. Even, perhaps especially, after a sequence of events forced him at a particular point to leave his native island and set up home in Naples. It was a dramatic separation, in some ways like the separation of a child from its mother. There was only one way, for the artist and the man, to make his homesickness less distressing, and that was to give it form in art, recomposing the fondest images, the beloved places, the moments of happiness or suffering, with fragments of coloured paper. And that’s what Attilio did, every day of his life, until seven years ago. Today his friends no longer come across him on the streets of the island, yet they continue to see him. He’s there, somewhere in the world, his eyes almost blind and his hands trembling. In the light of a lamp, he cuts out pieces of newspaper, and gives them a coat of light grey, for a collage with a subject that he loves to repeat, now that he’s far away. It’s his little room in the cottage at Sopramonte, with the crumbling ceiling and only one chair. The window is closed, the only coat hanger in the wardrobe is empty and the bed is unmade. As though after the guest has left.

Sguardi

Dai disegni a matita ai fogli colorati con le pennellate dell’acquerello per arrivare ai collage che tanto hanno caratterizzato la sua produzione artistica. È il percorso della mostra “Attilio Lembo. Sguardi” allestita negli spazi di Emporium, dove sono esposte oltre trenta opere tra nature morte, vedute dell’isola e interni. | From pencil drawings to watercolour paintings and finally the collages that were such a distinctive feature of his artistic production. That’s the itinerary for the exhibition “Attilio Lembo. Sguardi” being held in the rooms of the Emporium with over thirty works, including still lifes, island views and interiors.

Emporium – Via Valentino, 20b – 081 1886 5282 Fino al 10 agosto – orario d’apertura: tutti i giorni dalle 16.30 alle 19.30. Chiuso il martedì. | Until 10 August – opening times: every day except Tuesday, from 16.30 to 19.30. Closed on Tuesdays.