Inafferrabile emozione

Un mondo di mare e di rocce. Di sentimenti e forza della natura. È l’isola narrata da Raffaele La Capria, per gli amici Dudù

di Daniela Liguori | foto di Costantino Esposito

«Qui su quest’isola il cui nome è impresso nel mio, si formò il mito che inconsapevolmente vissi nella mia giovinezza. Qui si formò il mito della bella giornata e della dolce spensieratezza, il mito della Natura abitata dagli dei, le cui voci erano simili alle nostre gridate nell’ora meridiana». Sono le stesse parole dello scrittore italiano Raffaele La Capria, riportate in entrambi i libri che ha dedicato all’isola partenopea – Capri e non più Capri (Mondadori 1991) e L’isola il cui nome è iscritto nel mio (Minerva 2012) – a rivelare il suo profondo legame con Capri, che frequentò a partire dagli anni Cinquanta. Qui acquistò una casa ai piedi del Monte Solaro negli anni Ottanta «per inventarsi un’isola nell’isola» dove rifugiarsi dal frastuono di una Capri ormai divenuta affollata meta turistica e poter scrivere i suoi libri, tra i quali proprio Capri e non più Capri.

«Qui su quest’isola il cui nome è impresso nel mio, si formò il mito che inconsapevolmente vissi nella mia giovinezza. Qui si formò il mito della bella giornata e della dolce spensieratezza, il mito della Natura abitata dagli dei, le cui voci erano simili alle nostre gridate nell’ora meridiana». Sono le stesse parole dello scrittore italiano Raffaele La Capria, riportate in entrambi i libri che ha dedicato all’isola partenopea – Capri e non più Capri (Mondadori 1991) e L’isola il cui nome è iscritto nel mio (Minerva 2012) – a rivelare il suo profondo legame con Capri, che frequentò a partire dagli anni Cinquanta. Qui acquistò una casa ai piedi del Monte Solaro negli anni Ottanta «per inventarsi un’isola nell’isola» dove rifugiarsi dal frastuono di una Capri ormai divenuta affollata meta turistica e poter scrivere i suoi libri, tra i quali proprio Capri e non più Capri.

Tra i più significativi scrittori del secondo Novecento italiano, Raffaele La Capria nasce a Napoli l’8 ottobre 1922 ed esordisce appena trentenne con il romanzo Un giorno d’impazienza per raggiungere la fama con Ferito a morte, con cui ha vinto il Premio Strega nel 1961. Autore di numerosi romanzi, racconti e saggi letterari in forma narrativa e autobiografici, lo scrittore è stato anche co-sceneggiatore di molti film di Francesco Rosi, tra i quali Le mani sulla città (1963), C’era una volta (1967), Uomini contro (1970) e Cristo si è fermato ad Eboli (1979). Ha collaborato anche con Lina Wertmüller alla sceneggiatura del film Ferdinando e Carolina e all’adattamento per il cinema della commedia Sabato, domenica e lunedì di Eduardo De Filippo (1990).

È La Capria stesso a raccontarci di aver vissuto sull’isola partenopea tre epoche della sua vita che corrispondono ad altrettante epoche della vita di Capri.

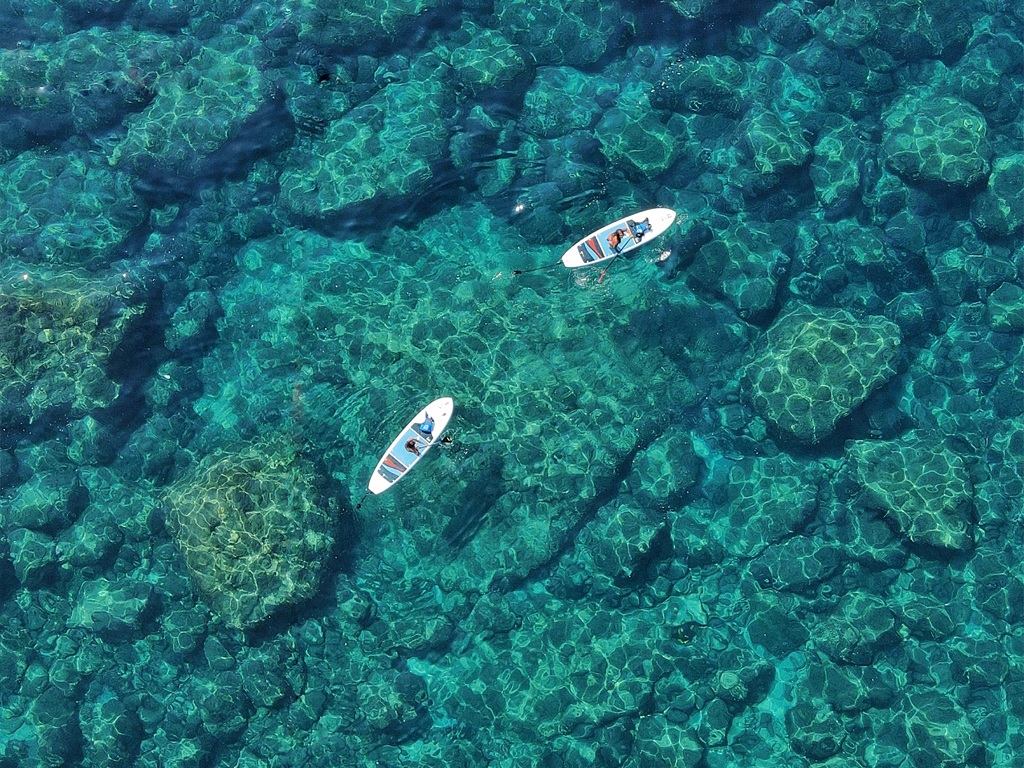

Lo scrittore giunse sull’isola per la prima volta negli anni Cinquanta. Sono gli anni della sua “squattrinata giovinezza”, quando Capri era frequentata da personaggi quali Norman Douglas, Curzio Malaparte, Alberto Moravia ed Elsa Morante. Al mattino – racconta – «bastavano pochi colpi di remo per trovarsi in una rada silenziosa circondata da altissime rocce strapiombanti, soli in mezzo a un mare trasparente dove per una misteriosa alchimia i verdi smeraldo, i blu cobalto e i teneri azzurri formavano sequenze musicali. E quando approdavi su una di quelle spiaggette candide come la neve nascoste tra gli scogli e ti sdraiavi nel bagliore accecante del sole, ti pareva di essere sbarcato su un atollo deserto». La sera si era invece soliti trovarsi in Piazzetta per assistere allo spettacolo dei numerosi personaggi che si riunivano intorno ai tavoli dei caffè: «il nuotatore si trasformava in viveur, il viveur in voyeur». Negli anni Sessanta La Capria ritornò a Capri con la moglie Ilaria e vi trovò un’atmosfera profondamente diversa perché l’isola si era già trasformata in affollata meta turistica: «era cominciata l’età del disincanto col rumore di un fuoribordo e lo scoppiettio dei cavalli a motore che solcavano il mare». Nonostante fossero già iniziati gli anni dell’invasione in massa dei turisti, La Capria decise di acquistare negli anni Ottanta una «casetta di contadini nell’arruffata campagna ai piedi del Monte Solaro». «è stata quella casa il mio rifugio, il mio piccolo Tibet, per più di quindici anni» scrive. «Lassù in quel romitaggio ho scritto il mio libro Capri e non più Capri, dove ho segnato i “pensieri del terrazzo” che andavano e venivano come nuvole sul Solaro, e il passaggio delle ore, la luce e l’ombra, il mutare dei colori sul mare. Lassù ho ricreato un po’ della Capri di una volta, lassù c’era silenzio, solitudine, contemplazione della natura».

Nonostante pensasse che Capri fosse un “soggetto impossibile” da raccontare, «un soggetto che scrittori ed artisti farebbero bene ad evitare, perché c’è qualcosa di troppo forte e sovrastante nella Natura di quest’isola, qualcosa di stregonesco, che rende ridicola e inadeguata ogni pretesa di catturarne la magia», il suo libro racconta proprio la magia di quest’isola “misteriosa”. «È la sua struttura stessa che è misteriosa» scrive. «È impossibile immaginare un simile groviglio geologico dove una tale quantità di punti di vista è concentrata in così poso spazio. Capri è capricciosa, labirintica, si avvolge su se stessa e si contorce in mille modi capziosi, basta cedere appena un po’ alle sue lusinghe e lo stesso luogo una volta si mostra con una faccia e un’altra volta con una completamente differente, perché la sua conformazione e anche il suo paesaggio tendono tranelli». Di questo paesaggio lo scrittore descrive le rocce imp ervie “piene di storia”, le sue grotte e le sue ca

ervie “piene di storia”, le sue grotte e le sue ca verne nelle acque, le sue anse ad anfiteatro popolate di barche e circoscritte da reti, le viti e i fichi d’India spaccati nella calura della campagna, il volo dei colombi e dei gabbiani che ne solcano il cielo. Ci racconta dell’intrecciarsi di tante vite che qui confluirono attratte da “un misterioso richiamo”: Norman Douglas, Friedrich Alfred Krupp, Jacques Fersen, Alberto Savinio, Monika Mann, Edwin Cerio. Ma La Capria ci racconta anche di come l’isola si sia trasformata in un luogo in cui può accadere di sognare di essere l’imperatore Tiberio per poter punire i proprietari dei motoscafi che affollano l’isola: «uno lo faccio imbrattare di nafta, un altro lo faccio seppellire tra i rifiuti, un altro viene costretto a bere un buon litrozzo di benzina, un altro è condannato a morire lentamente soffocato in un sacchetto di plastica, e così via, sempre applicando la pena dantesca del contrappasso». Ma Capri resta per lui sempre “uno dei punti più belli del globo”, in cui «si avverte meglio il minaccioso incombere di quello scadimento, di quel “disordine del mondo” che ci fa inevitabilmente pensare alla decadenza e alla fine di ogni cosa». Da un legame inscindibile con Capri è nato, dunque, questo libro che La Capria stesso confessa di aver scritto perché l’isola fa parte della sua “geografia personale”. «Il libro l’ho scritto anche – aggiunge – per dare conto della mia presenza qui, per parlare dello spirito del luogo e di quel che mi “ditta dentro”, e forse per entrare anche io nell’appartato cimetière marin della letteratura dedicata a Capri, e nella considerazione dei suoi cultori che non dimenticano facilmente chi è passato da queste parti e ha lasciato la sua testimonianza».

verne nelle acque, le sue anse ad anfiteatro popolate di barche e circoscritte da reti, le viti e i fichi d’India spaccati nella calura della campagna, il volo dei colombi e dei gabbiani che ne solcano il cielo. Ci racconta dell’intrecciarsi di tante vite che qui confluirono attratte da “un misterioso richiamo”: Norman Douglas, Friedrich Alfred Krupp, Jacques Fersen, Alberto Savinio, Monika Mann, Edwin Cerio. Ma La Capria ci racconta anche di come l’isola si sia trasformata in un luogo in cui può accadere di sognare di essere l’imperatore Tiberio per poter punire i proprietari dei motoscafi che affollano l’isola: «uno lo faccio imbrattare di nafta, un altro lo faccio seppellire tra i rifiuti, un altro viene costretto a bere un buon litrozzo di benzina, un altro è condannato a morire lentamente soffocato in un sacchetto di plastica, e così via, sempre applicando la pena dantesca del contrappasso». Ma Capri resta per lui sempre “uno dei punti più belli del globo”, in cui «si avverte meglio il minaccioso incombere di quello scadimento, di quel “disordine del mondo” che ci fa inevitabilmente pensare alla decadenza e alla fine di ogni cosa». Da un legame inscindibile con Capri è nato, dunque, questo libro che La Capria stesso confessa di aver scritto perché l’isola fa parte della sua “geografia personale”. «Il libro l’ho scritto anche – aggiunge – per dare conto della mia presenza qui, per parlare dello spirito del luogo e di quel che mi “ditta dentro”, e forse per entrare anche io nell’appartato cimetière marin della letteratura dedicata a Capri, e nella considerazione dei suoi cultori che non dimenticano facilmente chi è passato da queste parti e ha lasciato la sua testimonianza».

Tra ricordi e riflessioni

Da Fersen a Krupp, da Douglas ai Cerio passando per Villa Lysis, la scoperta della Grotta Azzurra e i genii del luogo. Personaggi-simbolo, suggestioni, atmosfere e leggende in un lirico, personalissimo itinerario storico, letterario, umano e di memorie.

Pubblicato per la prima volta da Mondadori nel 1991 e poi ristampato da La Conchiglia nel 2000, Capri e non più Capri è un testo ricco di ricordi e riflessioni dove la “Capri” e la “Non più Capri” coesistono. Dove la prima sta svanendo per far spazio a una realtà «malata, sofferente, disanimata» ma, scrive l’autore, «non vorrei che questo libro fosse letto con un sentimento di nostalgia per quello che Capri era e adesso non è più».| Memories and reflections. From Fersen to Krupp, from Douglas to Cerio, by way of Villa Lysis, the discovery of the Grotta Azzurra and the spirits of the place. Emblematic characters, impressions, atmospheres and legends in a lyrical, highly personal journey through history, literature, human lives and memories. Published for the first time by Mondadori in 1991 and then reissued by La Conchiglia in 2000, Capri e non più Capri is a book full of memories and reflections where the “Capri” and the “No Longer Capri” coexist. Where the former is disappearing to make room for a present reality that is “sick, suffering and dispirited”. But, as the author says: “I would not want this book to be read with a feeling of nostalgia for what Capri was, and is no longer.”

Da Fersen a Krupp, da Douglas ai Cerio passando per Villa Lysis, la scoperta della Grotta Azzurra e i genii del luogo. Personaggi-simbolo, suggestioni, atmosfere e leggende in un lirico, personalissimo itinerario storico, letterario, umano e di memorie.

Pubblicato per la prima volta da Mondadori nel 1991 e poi ristampato da La Conchiglia nel 2000, Capri e non più Capri è un testo ricco di ricordi e riflessioni dove la “Capri” e la “Non più Capri” coesistono. Dove la prima sta svanendo per far spazio a una realtà «malata, sofferente, disanimata» ma, scrive l’autore, «non vorrei che questo libro fosse letto con un sentimento di nostalgia per quello che Capri era e adesso non è più».| Memories and reflections. From Fersen to Krupp, from Douglas to Cerio, by way of Villa Lysis, the discovery of the Grotta Azzurra and the spirits of the place. Emblematic characters, impressions, atmospheres and legends in a lyrical, highly personal journey through history, literature, human lives and memories. Published for the first time by Mondadori in 1991 and then reissued by La Conchiglia in 2000, Capri e non più Capri is a book full of memories and reflections where the “Capri” and the “No Longer Capri” coexist. Where the former is disappearing to make room for a present reality that is “sick, suffering and dispirited”. But, as the author says: “I would not want this book to be read with a feeling of nostalgia for what Capri was, and is no longer.”

Elusive emotions

A world of sea and rocks. Of feelings and the power of nature. That is the island described by Raffaele La Capria (Dudù) for his friends

by Daniela Liguori • photos by Costantino Esposito

“Here, on this island, whose name is imprinted on mine, the legend that I experienced unconsciously in my youth, was formed. Here, the legend of the beautiful day and the sweet carefree life took shape, the legend of Nature inhabited by the gods, whose voices resembled our shouts during the afternoon hours.” These are the words of the Italian writer Raffaele La Capria that appear in the two books he dedicated to Capri: Capri e non più Capri (Mondadori 1991) and L’isola il cui nome è iscritto nel mio (Minerva 2012). The words reveal La Capria’s deep bond with Capri, where he has been going since the 1950s. He bought a house on Capri in the 1980s, at the foot of Monte Solaro, “to invent an island within an island for himself” where he could take refuge from the din of a Capri that had by now become a busy tourist destination, and where he could write his books, including Capri e non più Capri.

Raffaele La Capria, who was born in Naples on 8 October 1922, was one of the most important Italian writers of the second half of the 20th century and his debut novel, A Day of Impatience, came out when he was still in his thirties. He achieved fame when he won the Premio Strega in 1961 with The Mortal Wound. The author of numerous novels, stories and literary essays in narrative and autobiographical form, La Capria was also co-scriptwriter for many of Francesco Rosi’s films, including Hands Over the City (1963), More Than a Miracle (1967), Many Wars Ago (1970) and Christ Stopped at Eboli (1979). He also collaborated with Lina Wertmüller on the screenplay for the film Ferdinando and Carolina and on the film adaptation of the play Saturday, Sunday and Monday by Eduardo De Filippo (1990).

La Capria himself describes how he lived on Capri during three periods of his life, which corresponded with three periods in the life of Capri.

The writer arrived on the island for the first time during the 1950s. These were the years of his “penniless youth”, when Capri was frequented by people such as Norman Douglas, Curzio Malaparte, Alberto Moravia and Elsa Morante.

La Capria describes how, in the morning: “Just a few strokes of the oar would take you into a silent haven surrounded by steep overhanging cliffs, alone in the middle of a transparent sea where, by some mysterious alchemy, the emerald greens, cobalt blues and soft azures formed musical sequences. And when you landed at one of those snow-white beaches hidden between the rocks and you stretched out in the dazzling glare of the sun, you felt as though you had landed on a desert island.” In the evenings, people would go to the Piazzetta to watch the spectacle of all the people gathering around the café tables: “The swimmer turned into the viveur, and the viveur into the voyeur.” During the 1960s, La Capria returned to Capri with his wife Ilaria and found the atmosphere had completely changed, since the island had already become a crowded tourist destination: “The age of disenchantment had begun, with the noise of outboard motors and the sputtering of motorboat engines as they cut through the waves.” In the 1980s, even though the years of mass tourist invasions had already begun, La Capria decided to buy “a peasant cottage standing amid the rough countryside at the foot of Monte Solaro”. “It was my house of refuge, my little Tibet, for over fifteen years,” he wrote. “It was there in that hideaway that I wrote my book Capri e non più Capri, where I noted the “thoughts from the terrace” that came and went like the clouds over Monte Solaro, and the passing of the hours, the light and shade, and the changing colours of the sea. It was there that I re-created a little of the old Capri, where there was silence, solitude and contemplation of nature.”

He thought that Capri was an “impossible subject” to portray, “a subject that writers and artists would do well to avoid, because there is something too strong, too impending in the Nature of this island, something witch-like that makes any attempt to capture its magic ridiculous and inadequate”; yet despite this, his book still manages to portray the magic of this “mysterious” island. “It’s the structure itself that is mysterious,” writes La Capria. “It is impossible to imagine another such geological tangle, where so many points of view are concentrated within such a small space. Capri is capricious, labyrinthine; it winds around itself and twists itself up in a thousand captious ways. You just need to give in a little to its blandishments and the same place will show you one face at one time and another completely different face another time, because both its configuration and its landscape set traps.” The writer describes this landscape with its inaccessible rocks that are “full of history”, its grottos and caverns under the sea, its amphitheatre-shaped coves, crowded with boats and encircled with fishing nets, the vines and prickly pear, cracked in the sultry heat of the countryside, and the wheeling flight of doves and seagulls across the sky. He describes the intertwining of the many lives that flowed to Capri, drawn by “a mysterious call”: Norman Douglas, Friedrich Alfred Krupp, Jacques Fersen, Alberto Savinio, Monika Mann, Edwin Cerio. But La Capria also tells us how the island has been transformed into a place where people might dream of being the Emperor Tiberius in order to be able to punish the owners of the speedboats that crowd the waters around the island: “I would smear one with diesel oil, and have another buried among the rubbish; another would be forced to drink a full litre of petrol, and another condemned to die slowly, suffocated in a plastic carrier bag, and so on, always applying a Dantesque punishment of “contrapasso” or appropriate retribution.” But for La Capria, Capri always remains “one of the most beautiful spots on earth”, where “you perceive most clearly the looming threat of that decline, that ‘global disorder’ which inevitably makes us think of decay and the end of everything.” So this book, which La Capria confesses he wrote because the island is part of his “personal geography”, sprang from an unbreakable bond with Capri. He adds: “I also wrote the book to explain my presence here, to speak of the spirit of the place and of what it “says to me inside”, and perhaps also so that I too can become part of that secluded cimetière marin (graveyard of the sea) of literature dedicated to Capri, and in consideration of the Capri connoisseurs who do not easily forget those who have passed through these parts and have left their own traces.”

He thought that Capri was an “impossible subject” to portray, “a subject that writers and artists would do well to avoid, because there is something too strong, too impending in the Nature of this island, something witch-like that makes any attempt to capture its magic ridiculous and inadequate”; yet despite this, his book still manages to portray the magic of this “mysterious” island. “It’s the structure itself that is mysterious,” writes La Capria. “It is impossible to imagine another such geological tangle, where so many points of view are concentrated within such a small space. Capri is capricious, labyrinthine; it winds around itself and twists itself up in a thousand captious ways. You just need to give in a little to its blandishments and the same place will show you one face at one time and another completely different face another time, because both its configuration and its landscape set traps.” The writer describes this landscape with its inaccessible rocks that are “full of history”, its grottos and caverns under the sea, its amphitheatre-shaped coves, crowded with boats and encircled with fishing nets, the vines and prickly pear, cracked in the sultry heat of the countryside, and the wheeling flight of doves and seagulls across the sky. He describes the intertwining of the many lives that flowed to Capri, drawn by “a mysterious call”: Norman Douglas, Friedrich Alfred Krupp, Jacques Fersen, Alberto Savinio, Monika Mann, Edwin Cerio. But La Capria also tells us how the island has been transformed into a place where people might dream of being the Emperor Tiberius in order to be able to punish the owners of the speedboats that crowd the waters around the island: “I would smear one with diesel oil, and have another buried among the rubbish; another would be forced to drink a full litre of petrol, and another condemned to die slowly, suffocated in a plastic carrier bag, and so on, always applying a Dantesque punishment of “contrapasso” or appropriate retribution.” But for La Capria, Capri always remains “one of the most beautiful spots on earth”, where “you perceive most clearly the looming threat of that decline, that ‘global disorder’ which inevitably makes us think of decay and the end of everything.” So this book, which La Capria confesses he wrote because the island is part of his “personal geography”, sprang from an unbreakable bond with Capri. He adds: “I also wrote the book to explain my presence here, to speak of the spirit of the place and of what it “says to me inside”, and perhaps also so that I too can become part of that secluded cimetière marin (graveyard of the sea) of literature dedicated to Capri, and in consideration of the Capri connoisseurs who do not easily forget those who have passed through these parts and have left their own traces.”