La stagione caprese di Madame Bovary

È quella del 1866 quando Louise Colet, musa di Gustave Flaubert, approda sull’isola. Di lei restano la firma sul libro degli ospiti dell’hotel Pagano e il titolo di un romanzo mai pubblicato

di Giuseppe Aprea

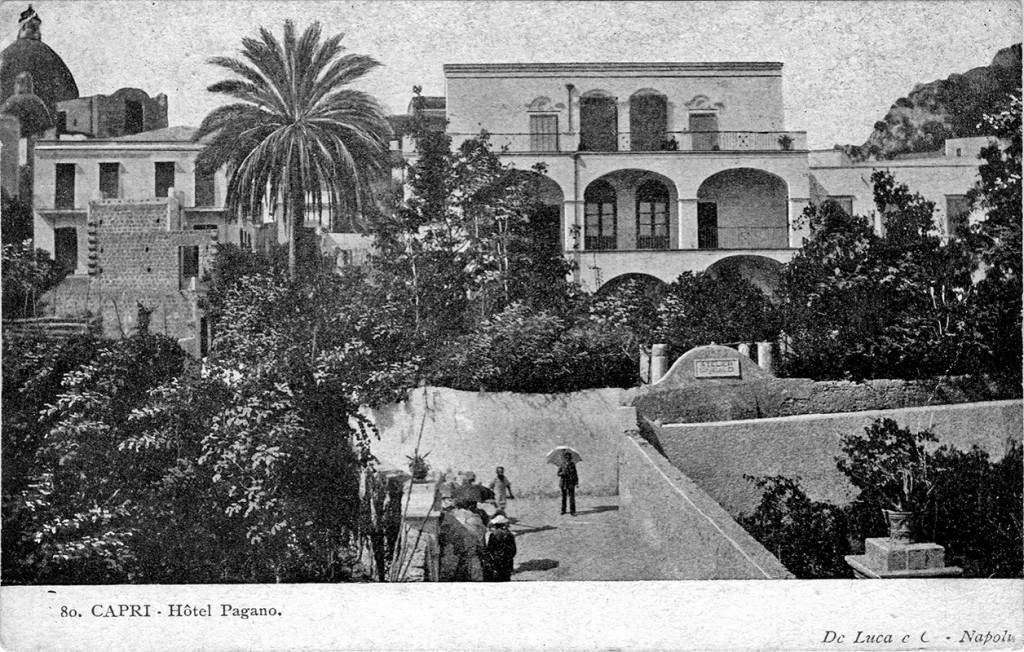

La portineria dell’hotel Pagano di Capri non aveva nulla in comune con la hall di un albergo cittadino, sia per le dimensioni ridottissime ed il colorito disordine che vi regnava, sia per il suo concièrge. Quest’ultimo, essendo lo stesso padrone di casa, non indossava alcuna divisa d’ordinanza che non fosse (almeno in estate) una camicia bianca con le maniche arrotolate e, seminascosto sotto un folto paio di baffi, un bel sorriso. Tutti, compresi i clienti stranieri che erano la maggioranza, lo conoscevano come “don Michele” e lui fin da subito li rassicurava sul fatto che potevano riferirsi a lui per qualsiasi cosa in qualsiasi momento. Ed è un fatto che a madame Bovary, che in albergo fece ingresso in una fortunata mattinata di agosto del 1866, di quelle chiare, azzurre e fresche che solitamente Dio comanda solo per settembre, tanto il luogo quanto l’accoglienza piacquero dal primo momento. Si sentì ospite attesa e coccolata come al Procope, il café al numero 13 di rue de l’Ancienne-Comédie a Parigi che era il suo preferito. Non a caso anche quello, fondato nel Seicento da un cuoco siciliano, profumava della fantasia e della gioia di vivere di quel popolo mediterraneo da lei prediletto tra tutti. Si badi bene che nei salotti della capitale di Francia tutti conoscevano da tempo il legame che univa Louise Colet alla terra natìa di Dante e, in quegli anni cruciali, al suo grande eroe, il generale Garibaldi. E allo stesso modo sapevano che nessun’altra se non lei, che Gustave Flaubert aveva amato perdutamente, ora si celava dietro quella sua Madame Bovary, anima in perenne tormento nel passaggio dal sogno all’azione, attratta tanto dalle passioni più pure, quanto dai godimenti più sfrenati. Era il ritratto della sua amante Louise, nessun dubbio. D’altra parte lui non ne faceva mistero: “la mia Musa”, la chiamava anche in pubblico. Ma che donna era quella Louise Colet capace di compiere un tale sortilegio su di un uomo?

La portineria dell’hotel Pagano di Capri non aveva nulla in comune con la hall di un albergo cittadino, sia per le dimensioni ridottissime ed il colorito disordine che vi regnava, sia per il suo concièrge. Quest’ultimo, essendo lo stesso padrone di casa, non indossava alcuna divisa d’ordinanza che non fosse (almeno in estate) una camicia bianca con le maniche arrotolate e, seminascosto sotto un folto paio di baffi, un bel sorriso. Tutti, compresi i clienti stranieri che erano la maggioranza, lo conoscevano come “don Michele” e lui fin da subito li rassicurava sul fatto che potevano riferirsi a lui per qualsiasi cosa in qualsiasi momento. Ed è un fatto che a madame Bovary, che in albergo fece ingresso in una fortunata mattinata di agosto del 1866, di quelle chiare, azzurre e fresche che solitamente Dio comanda solo per settembre, tanto il luogo quanto l’accoglienza piacquero dal primo momento. Si sentì ospite attesa e coccolata come al Procope, il café al numero 13 di rue de l’Ancienne-Comédie a Parigi che era il suo preferito. Non a caso anche quello, fondato nel Seicento da un cuoco siciliano, profumava della fantasia e della gioia di vivere di quel popolo mediterraneo da lei prediletto tra tutti. Si badi bene che nei salotti della capitale di Francia tutti conoscevano da tempo il legame che univa Louise Colet alla terra natìa di Dante e, in quegli anni cruciali, al suo grande eroe, il generale Garibaldi. E allo stesso modo sapevano che nessun’altra se non lei, che Gustave Flaubert aveva amato perdutamente, ora si celava dietro quella sua Madame Bovary, anima in perenne tormento nel passaggio dal sogno all’azione, attratta tanto dalle passioni più pure, quanto dai godimenti più sfrenati. Era il ritratto della sua amante Louise, nessun dubbio. D’altra parte lui non ne faceva mistero: “la mia Musa”, la chiamava anche in pubblico. Ma che donna era quella Louise Colet capace di compiere un tale sortilegio su di un uomo?

Con il cognome paterno di Revoil, la nostra era nata ad Aix-en-Provence, in quella Provenza allora lontana anni luce da Parigi e dai suoi salotti mondani e letterari. Ciò aveva fatto sì che al sogno giovanile di una luminosa carriera da scrittrice e da poetessa conseguisse la decisione di abbandonare presto i luoghi natii, colmi di grettezza e di conformismo – per respirare aria nuova nei salotti-bene della capitale. Louise aveva colto pertanto la prima occasione capitatale e sposato Hippolythe Colet, professore di flauto in procinto di trasferirsi a Parigi dove lo attendeva una prestigiosa cattedra al Conservatorio. Mai decisione si era rivelata più saggia. Le sue poesie avevano vinto uno dopo l’altro quattro premi al Concorso dell’Académie Française e la sua avvenenza attraeva più di uno sguardo. Questo secondo evento, in verità, aveva avuto più conseguenze del primo, se è vero che si era sparsa in giro la voce che la giuria dell’Académie era stata in qualche modo indotta ad attribuirle i premi non solo per l’indubbio merito, ma anche in seguito all’intervento di un suo amico piuttosto influente. E la nascita nel 1840 di Henriette, figlia di Louise però non riconosciuta da suo marito Hippolythe, ma da Victor Cousin filosofo ed effettivamente suo amante, aveva confermato le maldicenze.

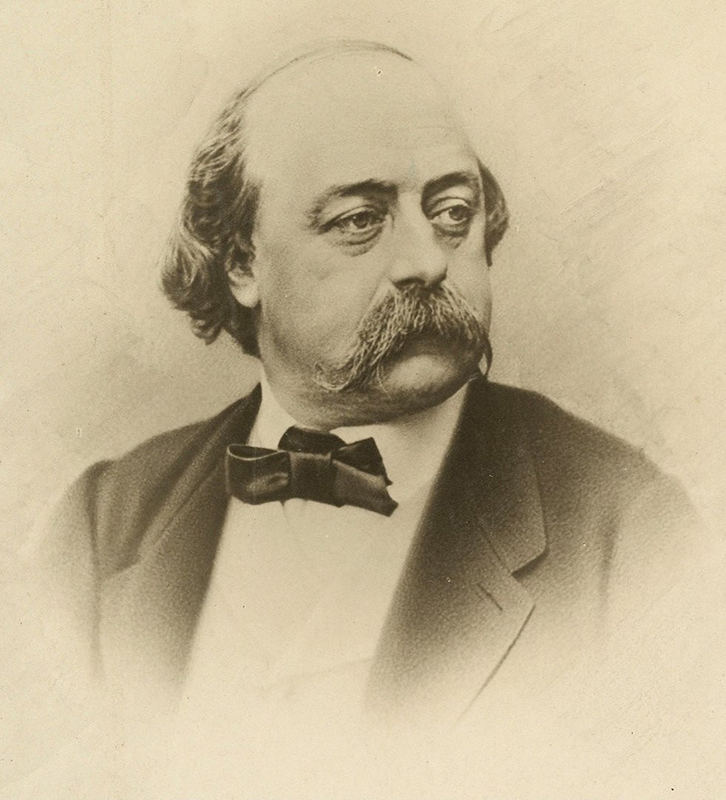

In effetti la nostra poetessa, non più giovanissima ma ancor piena di fascino, teneva saldamente in mano le redini della sua vita. «Ho seno, collo e spalle di grande bellezza – scriveva nel 1846 nel suo diario in una sorta di autoritratto letterario – la pettinatura mi attira molti complimenti. Ho la fronte alta, ben fatta, e gli occhi azzurro cupo, grandi, bellissimi quando ardono al fuoco del pensiero e delle sensazioni». Non c’è dunque da stupirsi al lungo elenco dei suoi ammiratori, quasi sempre uomini di cultura di grande fama, né da meravigliarsi se ad un certo punto quegli occhi ardenti e sensuali fecero un’altra vittima: Gustave Flaubert, allora ventiseienne e non ancora famoso scrittore. Dalla fine del 1846 al principio del 1855, i due diedero vita ad una relazione fatta di ondate di tenerezza e di lettere amorose, ma anche e soprattutto di irrefrenabile eros. «Ti ingozzerò di tutti i piaceri della carne, cosicché tu svenga e muoia. Quando sarai vecchia voglio che tu ricordi queste poche ore, e voglio che le tue ossa secche fremano di gioia nel rimembrarle» le scriveva lui.

Ma una volta intrapresa la scrittura di quello che sarebbe risultato il suo capolavoro, cioè Madame Bovary, mentre lei si dava anima e corpo agli ospiti del suo salotto parigino, in cui s’incontravano personaggi del calibro di Alfred de Musset e di Victor Hugo, lui si isolò a Croisset, presso Rouen, nella villa di famiglia. Il personaggio di Emma prese forma in quella casa, nel silenzio e nella solitudine della campagna, che solo l’improvviso ed imprevisto arrivo di Louise una sera riuscì a spezzare, ridestando dalle ceneri un amore che languiva nella lontananza. Per un po’ divampò il nuovo fuoco, poi sbocciò invece un intenso e intimo rapporto epistolare.

Non era ancora terminata la stesura della scoppiettante scena d’amore tra la protagonista e Rodolfo, il suo focoso amante, che Flaubert scrisse alla sua desiderata Musa. 23 dicembre 1853, venerdì notte, ore due. «Devo proprio amarti per scriverti stasera, perché sono sfinito. Dalle due del pomeriggio (salvo 25 minuti circa per cenare) scrivo la Bovary. Sono al loro amplesso, in pieno, al mezzo».

Nella realtà, come si diceva, il rapporto tra i due era alle ultime battute. E mentre Flaubert era costretto a difendersi in tribunale dall’accusa di “oltraggio alla morale pubblica e religiosa e ai buoni costumi” lei, piena di entusiasmo per il movimento risorgimentale italiano, partiva per il suo sognato primo viaggio in Italia: dal 1859, alla vigilia della spedizione dei Mille, fino al 1861. Inseguendo Garibaldi, giunse a Napoli il 10 settembre 1860, tre giorni dopo di lui. Lo incontrò a Palazzo d’Angri a via Toledo, dov’era alloggiato. Ai suoi occhi quell’uomo non rappresentava solo il capo di una rivoluzione, era la Poesia stessa della rivoluzione. Fu anche per questo che ne divenne l’amante, come si disse all’epoca? Chissà.

Dal 1862 al 1864 pubblicò i quattro volumi del suo L’Italie des Italiens; nell’estate del 1866 madame Bovary giunse a Capri. È tempo di dire che in quegli anni l’isola e l’albergo Pagano, con la sua grande palma, formavano una vera enclave artistica francese in Italia, tanti erano gli artisti transalpini che vi soggiornavano con frequenza: Henner, Benner, Hamon e Sain sono oggi i più noti tra essi. Conoscevano il luogo in tutti i suoi angoli più suggestivi, sensibili alla bellezza delle donne che posavano per loro e al buon vino bianco che si serviva al Pagano. Entusiasti per la tarantella. Benner era il più “caprese” di tutti: aveva sposato una di quelle fanciulle dalla pelle ambrata, Margherita, figlia proprio di quel don Michele Pagano padrone dell’albergo. Come lui aveva fatto il suo amico Sain, impalmando la bella Chiarella e scegliendo di spendere la vita con lei nella dolce Anacapri, dove il tempo scorre più lento.

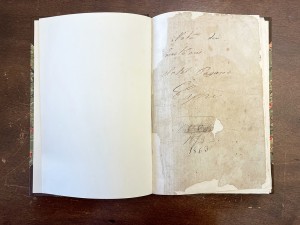

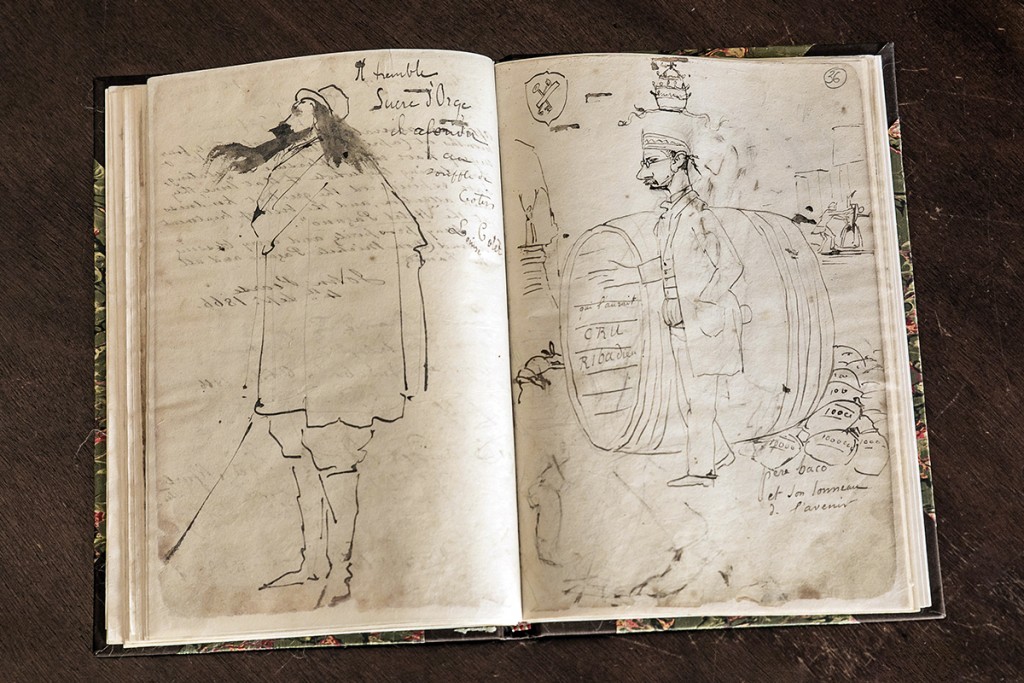

In questo piccolo angolo di Francia immerso nel Tirreno, in compagnia di questi allegri compatrioti, Louise (ovvero Emma) trascorse molto del suo tempo nell’isola, che si protrasse fino alle soglie dell’inverno. Quei giorni furono forse più di quanto avesse previsto e le ispirarono un romanzo di cui ci restano soltanto il titolo, Courtisanes de Capri e un gran rimpianto, in quanto il manoscritto con i primi capitoli fu rubato dalla sua stanza a Roma insieme ad altri importanti documenti. Letteralmente furibonda, accusò del furto la polizia papale, che d’altra parte la teneva d’occhio dal suo ingresso in città e poi ne scrisse al suo amico Garibaldi, che le assicurò un intervento di fidati amici romani che forse non avvenne mai. Il suo editore in Francia promise persino una lauta ricompensa a chi avesse riportato i preziosi manoscritti. Niente, ogni tentativo risultò vano. E a noi oggi non resta altro che riguardare la pagina del libro degli ospiti dell’albergo, dove c’è la firma di… madame Bovary sotto lo pseudonimo di Louise Colet. È proprio accanto alla caricatura di uno dei pittori della scatenata brigata francese di Capri, un polacco che essi chiamavano scherzosamente sucre d’orge. Ma di questo parleremo un’altra volta.

Testimoni preziosi

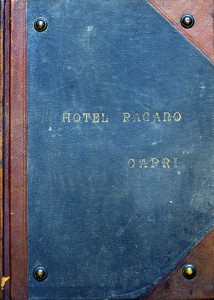

Firme, disegni, caricature. Date di arrivo e di partenza, luoghi di provenienza e di

Firme, disegni, caricature. Date di arrivo e di partenza, luoghi di provenienza e di destinazione. Sono un’infinità le notizie preziose che si possono trovare nei Registri e nei Libri degli ospiti dell’hotel Pagano conservati presso la Biblioteca del Centro Caprense Ignazio Cerio. Sono libroni di varie dimensioni con la copertina cartonata e pagine che mostrano tutti gli anni che hanno vissuto. Del primo, quello forse più famoso perché documenta la “riscoperta” della Grotta Azzurra che data 1826, esiste solo una fotocopia. Teodoro Pagano, che li aveva donati al Centro negli anni Ottanta, lo aveva voluto tenere per sé come caro ricordo. Ma gli fu rubato e mai più ritrovato. Sfogliarli è un tuffo nel tempo e nella storia di Capri. | Precious witnesses. Signatures, drawings and caricatures. Arrival and departure dates, places of origin and destinations. There is a wealth of valuable information to be found in the hotel registers and guestbooks of the Hotel Pagano, now kept in the library of the Centro Caprense Ignazio Cerio. These hardcover books of various sizes have pages that show the many long years they have lived through. Only a photocopy remains of the first book, which is perhaps the most famous since it documents the “rediscovery” of the Grotta Azzurra in 1826. Teodoro Pagano, who donated the books to the Centro in the 1980s, wanted to keep that one for himself as a cherished memory. But it was stolen from him and never recovered. Flicking through the pages offers a dip into the past and into the history of Capri.

destinazione. Sono un’infinità le notizie preziose che si possono trovare nei Registri e nei Libri degli ospiti dell’hotel Pagano conservati presso la Biblioteca del Centro Caprense Ignazio Cerio. Sono libroni di varie dimensioni con la copertina cartonata e pagine che mostrano tutti gli anni che hanno vissuto. Del primo, quello forse più famoso perché documenta la “riscoperta” della Grotta Azzurra che data 1826, esiste solo una fotocopia. Teodoro Pagano, che li aveva donati al Centro negli anni Ottanta, lo aveva voluto tenere per sé come caro ricordo. Ma gli fu rubato e mai più ritrovato. Sfogliarli è un tuffo nel tempo e nella storia di Capri. | Precious witnesses. Signatures, drawings and caricatures. Arrival and departure dates, places of origin and destinations. There is a wealth of valuable information to be found in the hotel registers and guestbooks of the Hotel Pagano, now kept in the library of the Centro Caprense Ignazio Cerio. These hardcover books of various sizes have pages that show the many long years they have lived through. Only a photocopy remains of the first book, which is perhaps the most famous since it documents the “rediscovery” of the Grotta Azzurra in 1826. Teodoro Pagano, who donated the books to the Centro in the 1980s, wanted to keep that one for himself as a cherished memory. But it was stolen from him and never recovered. Flicking through the pages offers a dip into the past and into the history of Capri.

Madame Bovary’s season on Capri

It was the summer of 1866 when Louise Colet, the muse for Gustave Flaubert’s great novel, arrived on the island. All that remains of her visit is her signature in the Hotel Pagano guest book and the title of a novel that was never published

by Giuseppe Aprea

The reception at the Hotel Pagano on Capri had nothing in common with your typical town centre hotel lobby, whether because of its tiny size and the lively chaos that always seemed to reign there, or because of its concierge. Since the concierge also happened to be the hotel owner, he didn’t wear any regulation uniform except a white shirt with the sleeves rolled up (in summer anyway) and, half-hidden beneath his large moustache, a warm smile. Everyone, including the foreign guests who were in the majority, knew him as “Don Michele”, and he would always reassure them right from the start that they could ask him for anything they needed at any time. And it’s clear that Madame Bovary, who entered the hotel one happy morning in August 1866, one of those clear, blue, fresh mornings that God usually only sends in September, was very happy both with the place and the welcome she received from the very beginning. She felt like an expected and pampered guest, just as she was at the Procope café, at number 13 Rue de l’Ancienne-Comédie, her favourite café in Paris. It is no coincidence that the café, founded by a Sicilian chef in the 17th century, was also imbued with that spirit of imagination and joie de vivre typical of the Mediterranean people, whom she loved more than any other. We should not forget that everyone in the Parisian salons would have long been aware of the bond linking Louise Colet with Dante’s native land, and, during those crucial years, with its great hero, General Garibaldi. And they also knew that it could be none other than Louise, the woman that Gustave Flaubert had been so desperately in love with, who was behind the title character of his Madame Bovary, a soul in perpetual torment in the transition from dreams to action, impelled as much by the purest passions as by the most unbridled pleasures. There is no doubt that it was a portrait of his lover, Louise. He made no secret of it, in any case: he used to call her “my Muse”, even in public. But what sort of woman was Louise Colet, who was capable of casting such a spell on a man?

Her maiden name was Revoil, and she was born in Aix-en-Provence, at a time when Provence was still light years away from Paris and its fashionable, literary salons. This meant that her youthful dreams of a shining career as a writer and poetess soon drove her to leave the place of her birth, so full of pettiness and conformism – to breathe the fresh air of the upper-class salons of Paris. So Louise seized the first opportunity offered to her and married Hippolyte Colet, a flute professor who was about to move to Paris, where a prestigious position at the Conservatoire was awaiting him. It proved the wisest decision she could have made. Her poetry had won her four awards one after another in the Académie Française Competition and her charm attracted more than a glance. This second event would actually have more repercussions than the first, if the rumours that were going around were true, that the jury of the Académie had been persuaded in some way to give her the prizes not only because of her undoubted merit, but also following the intervention of a rather influential friend of hers. The gossip was confirmed by the birth in 1840 of Louise’s daughter, Henriette, who was not acknowledged by her husband Hippolyte but by Victor Cousin, a philosopher and Louise’s lover, in fact.

Her maiden name was Revoil, and she was born in Aix-en-Provence, at a time when Provence was still light years away from Paris and its fashionable, literary salons. This meant that her youthful dreams of a shining career as a writer and poetess soon drove her to leave the place of her birth, so full of pettiness and conformism – to breathe the fresh air of the upper-class salons of Paris. So Louise seized the first opportunity offered to her and married Hippolyte Colet, a flute professor who was about to move to Paris, where a prestigious position at the Conservatoire was awaiting him. It proved the wisest decision she could have made. Her poetry had won her four awards one after another in the Académie Française Competition and her charm attracted more than a glance. This second event would actually have more repercussions than the first, if the rumours that were going around were true, that the jury of the Académie had been persuaded in some way to give her the prizes not only because of her undoubted merit, but also following the intervention of a rather influential friend of hers. The gossip was confirmed by the birth in 1840 of Louise’s daughter, Henriette, who was not acknowledged by her husband Hippolyte but by Victor Cousin, a philosopher and Louise’s lover, in fact.

Indeed, our poetess, no longer so young but still full of charm, kept a tight hold on the reins of her life. “I have a very beautiful bosom, neck and shoulders,” she wrote in her diary in a sort of literary self-portrait in 1846. “My coiffure attracts many compliments. I have a high, shapely forehead, and large, deep blue eyes, which are very beautiful when they glow with the fire of thought and feeling.” It’s not surprising, then, that she had a long list of admirers, almost all famous men of culture, nor is it surprising that at some point those glowing, sensual eyes captured another victim: Gustave Flaubert, then twenty-six years old and not yet a famous writer. From the end of 1846 to the beginning of 1855, the two of them entered a relationship full of waves of tenderness and amorous letters, but also, and especially, unbridled eros. “I want to gorge you with all the joys of the flesh, so that you faint and die. When you are old, I want you to recall those few hours, I want your dry bones to quiver with joy when you think of them,” he wrote to her.

But once he started writing what was to become his masterpiece, Madame Bovary, while Louise dedicated herself body and soul to the guests at her Parisian salon, where one might meet people such as Alfred de Musset and Victor Hugo, Flaubert shut himself away at Croisset, near Rouen, in his family villa. The character of Emma Bovary took shape in that house, in the silence and solitude of the countryside, only broken by the sudden and unexpected arrival of Louise one evening, rekindling from the ashes a love that had been languishing from their separation. For a while, a new passion flared up, but then an intense and intimate epistolary relationship blossomed.

Flaubert had not yet finished writing the sizzling love scene between Emma Bovary and Rodolfo, her impetuous lover, when Flaubert wrote to his beloved muse, on 23 December 1853, at 2 a.m. on a Friday night. “I must really love you to write to you tonight, because I’m exhausted. I’ve been writing Bovary since 2 in the afternoon (except for about 25 minutes for dinner). I’m in the middle of their love-making – the fullest of embraces.”

In reality, the relationship between Louise and Gustave was in its last stages, as we said earlier. And while Flaubert was forced to defend himself in court from the accusation of “outrage to public and religious morals and common decency”, Louise realized her long-cherished dream and set off on her first trip to Italy, full of enthusiasm for the Italian Risorgimento movement: she was to stay there from 1859, on the eve of the Expedition of the Thousand, until 1861. In pursuit of Garibaldi, she arrived in Naples on 10 September 1860, three days after his arrival in the city. She met him at Palazzo d’Angri in Via Toledo, where he was lodging. In her eyes, Garibaldi was not only the leader of a revolution, he was the whole poetic spirit of the revolution. Was that also why she became his lover, as was suggested at the time? Who knows?

Between 1862 and 1864, Colet published the four volumes of her L’Italie des Italiens; and in the summer of 1866 Madame Bovary arrived on Capri. At that time, a real French artistic enclave in Italy had become established on Capri and at the Hotel Pagano, with its large palm tree, since so many French artists used to stay there on a regular basis: Henner, Benner, Hamon and Sain are the best known today. They knew all the most beautiful corners of the island, and were susceptible to the charms of the lovely Capri women who posed for them, and of the good white wine served at the Pagano. They were fans of the tarantella. Benner was the most “Caprese” of them all: he had married one of those olive-skinned maidens, Margherita, the daughter of Don Michele Pagano in fact, the owner of the hotel. And his friend Sain had done the same, marrying the beautiful Chiarella, and choosing to spend his life with her in sweet Anacapri, where the time passes more slowly.

In this little corner of France immersed in the Tyrrhenian sea, in the company of her merry compatriots, Louise (or Emma) spent a lot of her time on the island, staying there until the approach of winter. Perhaps it was a longer stay than she had envisaged and it inspired a novel of which only the title remains: Courtisanes de Capri. The novel is a source of great regret, since the manuscript with the first chapters was stolen from her room in Rome, together with other important documents. Furiously angry, Louise accused the papal police of the theft: after all, they had been keeping an eye on her since she arrived in the city. Then she wrote to her friend Garibaldi about it, who assured her that some of his trusted Rome friends would intervene, which perhaps never happened. Louise’s French publisher even promised a generous reward for anyone who returned the precious manuscript. But it was all to no avail. And now, all we can do is look at the guestbook of the Pagano hotel, where there is the signature of… Madame Bovary, beneath the pseudonym of Louise Colet. Right next to the caricature of one of the artists of that wild French brigade on Capri, a Polish man whom they jokingly called sucre d’orge (barley sugar). But that’s a story for another time.