Verità, mezzeverità… e pallonismi

Capri è da sempre palcoscenico del fantastico. E nei suoi luoghi più famosi convivono mistero, sogno e fantasia

di Renato Esposito • illustrazioni di Fabio Finocchioli

Un emerito studioso di Norman Douglas, nel mese di ottobre, mi scrisse chiedendomi come si potesse tradurre in tedesco “pallonista caprese”. Dopo averci pensato un po’ azzardai “capresicher Ballmensch”, ben distante (o forse no?) dall’Übermensch (Superuomo) di nietzschiana memoria. Dopo mi sono chiesto: ma in inglese e francese? Capri-Ballman e Ballonist pensai. Ma è giusto far luce, in special luogo per i non addetti alle vicende isolane, per chiarire chi sono i Pallonisti capresi da cui deriva il termine pallonismo. In primis chiariamo la differenza tra Pallonisti e Pallisti. Pallonista è colui che inventa in maniera fantasiosa, gioiosa, creativa, attingendo alla grande tradizione dei racconti orali, “i cunti”, della storia caprese. Il Pallista inventa una bugia per tornaconto personale, per inganno, malizia. La “sindrome della jonta” (aggiunta) è alla base del Pallonista. In ogni racconto aggiunge sempre un particolare, una variante per rendere le vicende più accattivanti. Alla fine il racconto è totalmente cambiato, ma lui fa finta di non saperlo, è convinto che quella sia la verità, l’unica verità.

È innegabile che il pallonismo trova la sua genesi nella storia di Capri. Ha sempre affondato le sue radici in una terra di mezzo, i cui invisibili confini sono sempre il vero e il verosimile. La verità storica molte volte è triste, scarna, grigia, mentre il verosimile è variopinto, leggero, gioviale. L’isola da sempre è stata il palcoscenico del fantastico dove ogni mito si può rappresentare. Il suo spirito omerico, odisseo, pagano ha ispirato la creatività di improvvisati aedi che hanno creato nuove figure mitologiche, ancora presenti nel paesaggio e nell’immaginario collettivo isolano. Così nella cultura popolare, da generazione a generazione, le vicende dell’isola sono state raccontate inserendo nelle storie santi, sirene, diavoli, sfingi, fantasmi, centauri, pescatori e schiappaiuoli. Tutti insieme, liberamente. Personaggi storici e luoghi hanno assunto altre voci, altri colori in questo mondo fantastico del verosimile dove tutto è possibile. O quasi. Proviamo a percorrere insieme quei luoghi, popolati da tanti personaggi, punti di forza del pallonismo caprese.

Truths, half-truths and pallonisms

Capri has always been the setting for strange events. And its most famous places are home to mystery, dream and fantasy

by Renato Esposito • illustrations by Fabio Finocchioli

A distinguished Norman Douglas scholar wrote to me in October asking me if I could translate “pallonista caprese” (“Capri bullshitter”) into German. Having thought for a while, I ventured “capresicher Ballmensch”, a long way (or perhaps not?) from the Nietzschean Übermensch (Superman). But I should explain, especially for those who are not well-acquainted with Capri affairs, who these ‘Pallonisti’ are that give rise to the term pallonismo, or bullshit. First of all, we need to differentiate clearly between Pallonisti and Pallisti. A Pallonista is someone who invents things in an imaginative, humorous and creative way, drawing on the great tradition of oral narratives, “i cunti”, that have featured throughout Capri history. The Pallista, on the other hand, invents a lie in his or her own self-interest, in order to deceive or out of malice.

Behind every Pallonista is “supplement syndrome”. They always have to add a detail, a variation, to every tale, to make the story more fascinating. In the end, the story has become something entirely different, but they pretend not to realise that, convinced that the story they have told is the truth, the only truth. It can’t be denied that pallonismo has its origins in the history of Capri. Its roots have always been in that halfway land, whose invisible boundaries are truth and plausibility. Historical truth is often sad, lean and grey, whilst the plausible is multicoloured, light-hearted and humorous. The island has always been a stage for the imagination, where any legend can be acted out. Its Homeric, Odyssean, pagan spirit has inspired the creativity of extempore bards who have created new mythological figures, still present in the island’s landscape and collective imagination. So in popular culture, from generation to generation, the island’s life story has been told by inserting it into the stories of saints, sirens, devils, sphinxes, ghosts, centaurs, fishermen and schiappaiuoli (“catchers”). All freely mixed in together. Historical characters and places have taken on other voices, other colours in this imaginary world of the plausible, where everything is possible. Or almost. Let’s take a walk together through these places, populated by so many characters, the strong points of Capri bullshit.

Il re dei pallonisti | The king of bullshit

Ancora adesso a Capri quando si ascolta dire qualcosa di assurdo si esclama “sembra na palla i Bussett”. Ma chi era Bussett? Giuseppe Bussetti nacque a Capri dopo la Prima guerra mondiale e nella sua vita cambiò tanti mestieri. Ma le sue palle sono un vero capolavoro di fantasia e di umorismo non-sense. Nella sua antologia di palle quattro vengono ancora ricordate dal popolo caprese:

1) Un giorno due turisti incontrarono Bussetti affacciato al Belvedere di Tragara. Dopo una breve conversazione, la coppia gli chiese se sapesse quale fosse l’origine dei Faraglioni. Dopo pochi secondi, Bussetti rispose: «Certamente. Io li ho visti crescere».

2) Un giorno Bussetti andò a pescare al largo dei Faraglioni. Sentendosi la lenza pesante, iniziò a tirare lentamente. Dopo tanto tempo e immane fatica vide spuntare attaccato alla lenza un mostruoso oggetto meccanico: aveva pescato un sottomarino americano.

3) Durante la guerra, Bussetti era imbarcato su una nave ammiraglia così grande che, quando fu siglata la pace, a poppa della nave ancora si combatteva.

4) Dopo una coda di zefiro che aveva scosso l’isola con vento e pioggia, Bussetti decise di andare in chiesa per ringraziare la Madonna per lo scampato pericolo. Con sua grande meraviglia, lungo le scale della Piazzetta, trovò decine di polpi che scendevano verso il mare perduto.

Even now on Capri, if someone says something absurd, people will exclaim “that sounds like one of Bussett’s yarns”. But who was Bussett? Giuseppe Bussetti was born on Capri after the First World War and changed his trade many times over the years. But his palle, or yarns, are real masterpieces of imagination and humorous nonsense. From his anthology of yarns, four are still remembered by the Capri people:

1) One day, two tourists met Bussetti as he was looking out from the Belvedere di Tragara. After a brief conversation, the couple asked him if he knew the origins of the Faraglioni. After a few seconds, Bussetti answered: “Of course. I watched them grow up there.”

2) One day, Bussetti went fishing in the sea off the Faraglioni. He felt a tug on the fishing line and began to reel it in slowly. After a long time and immense effort, he saw a colossal mechanical monster emerge, attached to his fishing line: he had caught an American submarine!

3) During the war, Bussetti was on board such an enormous naval flagship that when the peace was signed, people were still fighting at the stern of the ship.

4) After the passing of a west wind that had buffeted the island with wind and rain, Bussetti decided to go to church to thank the Madonna for his escape from danger. To his amazement, the steps of the Piazzetta were covered with masses of octopuses, trying to find their way back down to the sea.

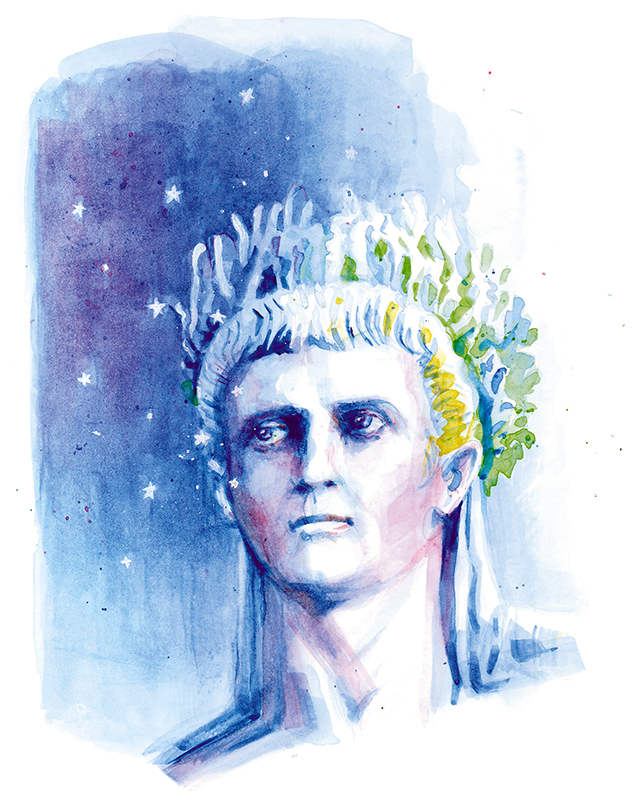

Tiberio e Villa Io | Tiberius and the Villa Io

In principio ci fu Tiberio. Le fantasiose, lussuriose e nefande vicende dell’imperatore romano, eroe affascinate e maledetto, hanno condizionato la storia turistica di Capri. I primi viaggiatori illuministi sono approdati sull’isola alla ricerca delle tracce delle scelleratezze tiberiane. I resoconti della vita caprese dell’imperatore degli storici Tacito e Svetonio hanno influenzato per secoli storici e archeologi creando una “sindrome di Tiberio”. I due storici lo descrivono come un ubriacone (Biberius) perché beveva il vino senza allungarlo, alla spasmodica ricerca dei piaceri sessuali più raffinati, rinchiuso in una villa consacrata a Jovis.

Molte selvae si trasformano in efebei. Ci descrivono perfino i quadri a tema sessuale che erano alle pareti di Villa Io che diventerà, per errore o per onorare Zeus, Villa Jovis. E che dire del numero delle ville imperiali a Capri? Dodici, come le divinità dell’Olimpo. Ma queste dodici ville imperiali dove sono collocate? Con tesi discordanti gli  archeologi ne indicano sei: Villa Io, Palazzo a Mare, Damecuta, Tragara, sulla collina del Castiglione e Monte San Michele. Molte villae fructuaria o di notabili vengono subito indicate come ville imperiali. L’arx, la fortezza, dove Tiberio ha vissuto a lungo e guidato l’impero era una rocca alta, dura e inaccessibile, priva delle guglie e degli ornamenti architettonici concepiti dal pittore e architetto tedesco Karl Weichardt. Dura e impenetrabile, come il carattere di un uomo che voleva vivere lontano da Roma, amareggiato, condannato a regnare mentre desiderava solo leggere, circondarsi di eruditi e osservare le stelle e i pianeti di quella galassia dove si ha l’illusione d’intravedere la felicità perduta.

archeologi ne indicano sei: Villa Io, Palazzo a Mare, Damecuta, Tragara, sulla collina del Castiglione e Monte San Michele. Molte villae fructuaria o di notabili vengono subito indicate come ville imperiali. L’arx, la fortezza, dove Tiberio ha vissuto a lungo e guidato l’impero era una rocca alta, dura e inaccessibile, priva delle guglie e degli ornamenti architettonici concepiti dal pittore e architetto tedesco Karl Weichardt. Dura e impenetrabile, come il carattere di un uomo che voleva vivere lontano da Roma, amareggiato, condannato a regnare mentre desiderava solo leggere, circondarsi di eruditi e osservare le stelle e i pianeti di quella galassia dove si ha l’illusione d’intravedere la felicità perduta.

In the beginning there was Tiberius. The bizarre, lascivious and infamous stories about this Roman emperor, both fascinating hero and cursed villain, have conditioned the tourist history of Capri. The first Enlightenment travellers arrived on the island in search of evidence of Tiberius’s villainies. The accounts of the emperor’s life on Capri provided by the historians Tacitus and Suetonius have influenced historians and archaeologists for centuries, creating a “Tiberius syndrome”. The two historians describe him as a drunkard (Biberius) because he drank wine without diluting it, in the frantic search for the most refined sexual pleasures, shut away in a villa consecrated to Jove (Jupiter). Many of the selvae (wooded groves) became gyms for training adolescent boys (ephebos). They even describe the sexually-explicit paintings on the walls of the Villa Io, that was to become, whether through error or to honour Zeus, Villa Jovis (or ‘Jove’). And what about the number of imperial villas on Capri? Twelve, the same number as the gods on Olympus. But where were these twelve imperial villas located? There is disagreement among archaeologists, but six have been indicated: Villa Io, Palazzo a Mare, Damecuta, Tragara, and the hillsides of Castiglione and Monte San Michele. Many of the villae fructuaria (farmhouse villas) or villas belonging to important personages can be immediately identified as imperial villas. The arx, the fort where Tiberius lived for a long time and ruled the empire was a high, stern, inaccessible fortress, with none of the spires or architectural ornamentation dreamed up by the German artist and architect Karl Weichardt. It was hard and impenetrable, like the character of the man who wanted to live far away from Rome, embittered and condemned to rule when he only wanted to read, to surround himself with learned men, and to observe the stars and planets of that galaxy where he had the illusion that he could glimpse his lost happiness.

Piazzetta

La Chiazza e i chiazzieri sono il motore immobile dei racconti capresi. Ogni centimetro quadrato delle centinaia di basoli della Piazza cela geloso un ricordo, un segreto inconfessabile. In questo teatrino del mondo, ogni semplice pettegolezzo subisce una metamorfosi e si consacra al vero sul palcoscenico della mondanità. D’estate giornalisti, influencer e presenzialisti stagionati ingigantiscono senza pudore ogni minimo battito d’ali di questo ombelico del mondo. D’inverno, questo palcoscenico cosmopolita diventa territorio dei chiazzieri isolani. Ogni piccolo accadimento viene analizzato dai professionisti del “cucioescucio”. Nel vocabolario caprese si usa l’espressione “si dice a chiazza” per certificare una notizia presumibilmente vera. Ma anche la gioiosa Piazzetta ha il suo lato oscuro. È l’enorme caverna-sottopassaggio costruito negli anni Settanta e mai terminato che si estende  sotto la sua pavimentazione lavica. Per i capresi è il bunker segreto. Non si sa mai.

sotto la sua pavimentazione lavica. Per i capresi è il bunker segreto. Non si sa mai.

The Chiazza (Piazza) and the chiazzieri are the immovable engine that drives all Capri stories. Every square centimetre of the hundreds of basoli (stone slabs) in the Piazza jealously conceal a memory, a secret never to be confessed. In this little theatre of the world, every simple piece of gossip undergoes a metamorphosis and becomes the sacred truth on this high society stage. In summer, journalists, influencers and seasoned presenzialisti (people who are present at every social event) shamelessly exaggerate the slightest little tremor in this navel of the world. In winter, this cosmopolitan stage is reclaimed by the island’s chiazzieri. Every little happening is picked over by the professional gossip-mongers. The vocabulary of Capri includes the phrase “Si dice a chiazza…” (‘They’re saying in the piazza…’), supposedly to certify that something is true. But even the carefree Piazzetta has its dark side: the enormous cavern-subway they started building in the 1970s and never finished, that extends beneath the volcanic stone slabs of the piazza. For the Capri inhabitants it’s the secret bunker. You never know.

Grotta Azzurra

Il fuoco azzurro di una grotta caprese poco si addice alla verità. Questa grotta, antico ninfeo augusteo-tiberiano, ha subito nei secoli continue metamorfosi linguistiche dove la fantasia ha regnato regina. Chiamata dai capresi già nel 1500 “Grotta di Gradola” si trasformerà nella “Grotta ru Riavolo” (diavolo) nei secoli successivi. Considerare tutto quello che era attinente a Tiberio demoniaco e sconsacrato è stata una costante della storia di Capri. Certamente i primi pescatori che a nuoto entrarono nella Grotta Azzurra s’immersero in uno scenario inquietante: ombre di statue di divinità marine nei riflessi azzurri dell’acqua. Pensare al diavolo fu naturale.

È emblematica la storia che ci racconta lo scrittore Enzo Petraccone. Un pescatore fiocinò un enorme pesce davanti all’antro della grotta. All’improvviso tutto in mare si colorò di rosso, l’arpione si liquefece, poi di seguito vide rinsecchire il suo braccio e poi velocemente tutto il suo corpo. La “scoperta” della Grotta Azzurra nel 1826 da parte degli artisti August Kopisch ed Ernst Fries permise all’albergatore caprese Giuseppe Pagano di sdoganare la grotta e trasformarla in un culto romantico dove mistero, sogno e fantasia convivono magicamente. In questa ottica, i cunicoli che si aprono in fondo diventeranno passaggi segreti per raggiungere la Villa di Damecuta.

The idea that this Capri grotto takes its name from blue fire has little truth in it. The grotto, an ancient Augustan-Tiberian nymphaeum, has undergone several linguistic metamorphoses over the centuries under the sway of the imagination. By 1500 the Capri inhabitants were calling it the “Grotta di Gradola” which then became the “Grotta ru Riavolo” (Grotto of the Devil) in subsequent centuries. It has been a constant theme in the history of Capri to consider everything related to Tiberius to have been satanic and sacrilegious. Certainly, the first fishermen who swam into the Grotta Azzurra found themselves immersed in a disturbing scene: the shadowy forms of the statues of sea gods could be seen through the blue reflections of the water. It was quite natural for them to think of the devil.

The story that writer Enzo Petraccone tells us is typical of that atmosphere. A fisherman speared an enormous fish at the entrance to the grotto. Suddenly, everything in the sea turned red, the harpoon turned to liquid and he saw his arm shrivel up, followed immediately by his whole body. The “discovery” of the Grotta Azzurra in 1826 by the artists August Kopisch and Ernst Fries allowed the Capri hotel keeper Giuseppe Pagano to free the grotto from its burden of superstition and turn it into a romantic cult, where mystery, dreams and fantasy magically co-exist. Under this scenario, the tunnels that open up at the bottom of the cave became secret passageways for reaching the Damecuta Villa.

Scala Fenicia | The Phoenician steps

Ma i Fenici quando sono sbarcati a Capri? Non si sa e mai si saprà. Sicuramente per i dotti capricentrici ante litteram era ovvio che sull’isola più bella del mondo fossero sbarcati, tra i tanti, anche i Fenici. E così, quella ciclopica scala nella roccia che collega Capri e Anacapri divenne Scala Fenicia. In verità la lunghissima scala (attualmente 921 scalini) fu costruita dai coloni greci provenienti da Cuma che nel sesto secolo a.C. si stabilirono in località Torra nei pressi delle sorgenti e dell’approdo della Grande Marina. Scala greca e non fenicia, quindi. Ma è innegabile che questa splendida opera che termina con la famosa Porta della Differentia, antico accesso al Comune di Anacapri, è uno dei luoghi dove i racconti delle famiglie di Palazzo a Mare e di quelle anacapresi tramandano l’avvistamento di eccentrici fantasmi. Cavalieri con spade, eleganti uomini con bastone ed eteree signore dalla pelle diafana sono stati i protagonisti di terrificanti incontri ravvicinati lungo le scale. Sono questi “gli spiriti maligni” citati ancora oggi nella mattonella maiolicata alla fine della scala? Non esattamente. Quelli erano gli spiriti della peste e delle epidemie che secoli orsono tanti morti mietevano nella povera popolazione.

But when did the Phoenicians arrive on Capri? We don’t know, and we never will know. For the early Capri-centred scholars, it was obvious that the Phoenicians must have been among the many peoples who came to the most beautiful island in the world. So that huge staircase in the rock that links Capri with Anacapri became the Scala Fenicia (Phoenician Steps). In reality, the ultra-long staircase (now 921 steps) was built by the Ancient Greek settlers who came from the Cumae settlement in the sixth century B.C.E. and settled in the Torra area, near the springs and the Grande Marina harbour. So they are Greek stairs rather than Phoenician. But it is undeniable that this splendid construction that ends in the famous Porta della Differenza (the Gate of Discord), the former entrance gate to the town of Anacapri, is one of the places mentioned in the stories passed down by families from Palazzo a Mare and Anacapri where eccentric ghosts have been seen. Knights with swords, elegant gentlemen carrying canes, and ethereal ladies with diaphanous skin have featured in terrifying encounters on the steps. Are these the “evil spirits” still mentioned today in the majolica tile situated at the end of the staircase? Not exactly. Those were in fact the spirits of the plague and epidemics that killed so many of the poor population over the centuries.

Faraglioni

Se navigate in internet trovate che i nomi che indicano i Faraglioni sono vari e interscambiabili. Con il nome Stella e Saetta vengono denominati a turno sia il Faraglione di terra (che non è un Faraglione) sia quello di Mezzo. I nomi dei Faraglioni sono Stella (il non-Faraglione), di Mezzo e Scopolo. Saetta è la distanza (otto metri) tra il Faraglione di Mezzo e Scopolo. Ma è la nascita dei Faraglioni che ha scatenato la fantasia di pittori, poeti e scrittori. Questi giganteschi massi di roccia carsica distaccatisi più di 200mila anni fa dalla terraferma per terremoti e sprofondamenti geologici, attraverso i dipinti romantici di Frederich Preller (esposti nella sala consiliare del Comune di Capri) entrano a far parte del mito omerico-odisseo caprese. Si capisce così che Ulisse dopo aver  accecato Polifemo, che viveva in una grotta (Grotta della Paglia di Matermania), con lo sperone di roccia chiamato Pizzolungo fugge via con le sue navi e il ciclope, pazzo d’ira, per fermarlo getta in mare tre enormi rocce, che d’allora saranno chiamate Faraglioni. Più poetica e drammatica è la storia di Leucopetra, splendida fanciulla dalla pelle bianca come l’avorio. Per conquistare il suo amore, due giganti, Sebeto e Vesevo, si combattono seminando in ogni luogo morte e distruzione. Disperata, Leucopetra si getta in mare e muore. Ma gli dei, commossi da tale gesto, la trasformano nei Faraglioni, divinità dalle bianche rocce.

accecato Polifemo, che viveva in una grotta (Grotta della Paglia di Matermania), con lo sperone di roccia chiamato Pizzolungo fugge via con le sue navi e il ciclope, pazzo d’ira, per fermarlo getta in mare tre enormi rocce, che d’allora saranno chiamate Faraglioni. Più poetica e drammatica è la storia di Leucopetra, splendida fanciulla dalla pelle bianca come l’avorio. Per conquistare il suo amore, due giganti, Sebeto e Vesevo, si combattono seminando in ogni luogo morte e distruzione. Disperata, Leucopetra si getta in mare e muore. Ma gli dei, commossi da tale gesto, la trasformano nei Faraglioni, divinità dalle bianche rocce.

If you carry out an internet search, you’ll find that there are many different, interchangeable names for the Faraglioni. Both the Faraglione di Terra, the one that is joined to the land (which is not a true Faraglione), and the Faraglione di Mezzo, are sometimes called Stella or Saetta. The actual names of the Faraglioni are Stella (the non-Faraglione), Mezzo and Scopolo. Saetta is the 8-metre distance between the Mezzo and Scopolo Faraglioni. But it is the origin of the Faraglioni that has sparked the imagination of artists, poets and writers. These gigantic masses of karst rock that separated from the land over 200,000 years ago as a result of earthquakes and geological collapse, have been turned into Capri Homeric-Odyssean legend through the romantic paintings of Frederich Preller (on display in the Capri town council chamber). So we see that after Odysseus blinded the cyclops Polyphemus, who lived in the Grotta della Paglia in Matermania, using the spur of rock called Pizzolungo, and then escaped with his ships, the cyclops, maddened with anger, hurled three enormous rocks into the sea to stop him, and ever since then, these three rocks have been called the Faraglioni. The story of Leucopetra, a beautiful maiden with skin as white as ivory, is even more poetic and dramatic.

Two giants, Sebeto and Vesevo, fought to win her love, sowing death and destruction everywhere they went. In desperation, Leucopetra threw herself into the sea and died. But the gods, moved by her action, turned her into the Faraglioni, the goddess of the white rocks.

Giardini di Augusto e via Krupp | The Augustus gardens and via Krupp

Quante volte passeggiando tra i viali fioriti dei Giardini di Augusto abbiamo sentito raccontare a gruppi di turisti la storia che in quel luogo «sorgeva la villa più bella dell’imperatore Augusto, di cui si possono ancora adesso ammirare queste preziose statue» e indicando l’albergo Villa Krupp «qui Alfred Krupp, l’uomo più ricco al mondo, costruì la sua principesca villa…». Difficilmente troverete un luogo di Capri, come i Giardini di Augusto, dove la verità viene quotidianamente distorta. Krupp, agli inizi del XX secolo, volle creare per sé un giardino d’inverno con piante grasse rare, alla cui entrata troneggiavano due grossi leoni in marmo che adesso sono nella parte superiore del parco. Senza dubbio l’industriale tedesco fu la vittima più illustre della sindrome di Tiberio. Il più grande benefattore dell’isola, cittadino onorario, fu travolto da uno scandalo che lo porterà al suicidio. Il pallonismo giornalistico prezzolato trasformerà la Grotta di Fra’ Felice a via Krupp, dove egli goliardicamente incontrava i suoi amici capresi per bere vino e mangiare, in un luogo di turpitudini e orge di tiberiana memoria. Così dopo lo scandalo e la Prima guerra mondiale i giardini Krupp divennero Giardini di Augusto.

dove la verità viene quotidianamente distorta. Krupp, agli inizi del XX secolo, volle creare per sé un giardino d’inverno con piante grasse rare, alla cui entrata troneggiavano due grossi leoni in marmo che adesso sono nella parte superiore del parco. Senza dubbio l’industriale tedesco fu la vittima più illustre della sindrome di Tiberio. Il più grande benefattore dell’isola, cittadino onorario, fu travolto da uno scandalo che lo porterà al suicidio. Il pallonismo giornalistico prezzolato trasformerà la Grotta di Fra’ Felice a via Krupp, dove egli goliardicamente incontrava i suoi amici capresi per bere vino e mangiare, in un luogo di turpitudini e orge di tiberiana memoria. Così dopo lo scandalo e la Prima guerra mondiale i giardini Krupp divennero Giardini di Augusto.

How many times, strolling through the flowery avenues of the Augustus Gardens, have we heard someone telling a group of tourists the story that this was the site where “the most beautiful of the Emperor Augustus’s villas stood, and you can still admire these fine statues from it today”; or, pointing to the Hotel Villa Krupp: “This is where Alfred Krupp, the richest man in the world, built his magnificent villa …”. It would be difficult to find a place on Capri where truth is more frequently distorted on a daily basis than the Augustus Gardens. In the early 20th century, Krupp wanted to create a winter garden for himself with rare succulent plants and two large marble lions guarding the entrance: these lions are now located in the upper part of the park. There is no doubt that the German industrialist was the most illustrious victim of Tiberius syndrome. Krupp, the most generous benefactor of the island and an honorary citizen, was engulfed by a scandal that was to lead to his suicide. The stories concocted by hacks working for the gutter press transformed the Grotta di Fra’ Felice in Via Krupp, where Krupp used to get together with his Capri friends for boisterous eating and drinking sessions, into a place of depravity and Tiberian-style orgies. After that scandal, and in the wake of the First World War, the Krupp gardens became the Augustus Gardens.

I pescatori che sulle barchette a remi accompagnavano i turisti a fare il giro dell’isola e alla visita della Grotta Azzurra sono stati i capostipiti del pallonismo insulare. Remando per tante ore, inanellavano storie di mare e di terra, cambiando nel tempo il nome delle grotte con cromatismi alla moda. Fu così che la Grotta del Turco diventò verde, quella successiva rossa e quella vicino alle alte rocce che ricordano due orecchie d’asino Grotta Bianca. La Bella Carmelina che ai primi del Novecento guidava i turisti negli scavi di Villa Jovis, sovrapponeva, con sempre nuove aggiunte a sorpresa, storie di Tiberio, Seiano, diavoli, schiavi e santi. Adesso, i pallonisti moderni hanno meno fantasia. Le loro storie sono sempre più standardizzate alle richieste di un turismo mordi e fuggi. Così la statua dello scugnizzo Gennarino creata negli anni Sessanta, che saluta i turisti nell’approdo a Capri, è diventata una statua antica trovata nella Grotta Azzurra, è nata una spiaggia del Bunga-Bunga, sono state individuate statue di roccia miracolose e Sophia Loren è proprietaria della villa in pietra (Villa Julmira) con vista sulla baia di Marina Piccola. E così, di palla in palla, anche i poveri Faraglioni hanno “indossato” il nome di due famosi stilisti italiani.

The fishermen who took tourists in rowing boats on tours around the island and on visits to the Grotta Azzurra were the initiators of Capri pallonismo. As they rowed for hour after hour, they spun tales of the sea and land, changing the names of the grottos over time, as colour fashions changed. So the Grotta del Turco became the Green Grotto, the one after it the Red Grotto, and the grotto near the high rocks resembling the two ears of a donkey, the White Grotto. The Bella Carmelina who used to guide tourists around the Villa Jovis excavations in the early years of the 20th century, used to layer in, always with some new and surprising additions, stories of the emperors Tiberius and Sejanus, of devils, slaves and saints. Nowadays, the modern bullshitters have less imagination. Their stories are ever more standardized to meet the demands of Grab&Go tourism. So the statue of the street urchin Gennarino created in the 1960s, who greets tourists on their arrival on Capri, has become an ancient statue that was found in the Grotta Azzurra; there is now a Bunga-Bunga beach; miraculous statues in the rock have been identified; and Sophia Loren is the owner of the stone villa (Villa Julmira) with a view over the bay of Marina Piccola. And so on, one piece of bullshit after another, so that even the poor Faraglioni have “donned” the names of two famous Italian designers.