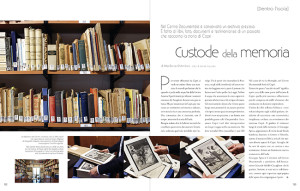

Custode della memoria

Nel Centro Documentale è conservato un archivio prezioso. È fatto di libri, foto, documenti e testimonianze di un passato che racconta la storia di Capri

di Marilena D’Ambro | foto di Davide Esposito

Per restare affascinati da Capri ci vuole un attimo. Basta una manciata di secondi per lasciare che lo sguardo si perda nelle acque blu della Grotta Azzurra. E pochi istanti per sfiorare i contorni maestosi dei Faraglioni durante una gita in barca. Ma per innamorarsi di Capri, per maturare un sentimento così intenso e radicato, serve tutta la vita e una conoscenza profonda. Una conoscenza che si costruisce con il tempo, attraverso la storia dell’isola.

Bisogna andare oltre le bellezze naturali che costellano questa terra dai contorni femminei e sollevare quel velo invisibile che l’avvolge. Tra le pareti che circondano la Piazzetta, tra gli edifici medievali nel centro storico riecheggiano voci e passi di persone che hanno reso l’isola quella che è oggi. Perfino le acque che accarezzano le coste capresi riportano alla luce tracce di un’epoca lontana.

Gli stessi uomini e donne che vivono questo luogo sono portatori di un passato prezioso e lo ripercorrono quasi inconsapevolmente, diretti verso un presente e un futuro reso possibile grazie a chi li ha preceduti. Ecco, amare Capri vuol dire intraprendere un lungo viaggio nella sua memoria. Ma dove trovarla? Dove riacciuffare i suoi fili?

Nel cuore di via Le Botteghe, nel Centro Documentale Isola di Capri.

Entrare in questa “casa dei ricordi” significa aprire una delle tante porte dell’anima di Capri, quella più nascosta e affascinante perché composta da mille sfumature che conducono in direzioni sorprendenti.

L’odore dei libri solletica l’olfatto e i tanti volumi disposti sugli scaffali parlano, desiderosi di raccontare una caratteristica inesplorata, un fatto, un avvenimento che interessa Capri. A guidare il visitatore lungo le strade della memoria c’è Giuseppe Aprea, appassionato di storia locale fin da bambino, laureato in Lettere e Filosofia, autore di numerosi libri e articoli che narrano diversi aspetti di Capri. Accoglie chi ha sete di sapere con un sorriso e una scommessa: donare un frammento ancora sconosciuto dell’isola.

Giuseppe Aprea è il direttore del Centro Documentale e presidente dell’Associazione Culturale Achille Ciccaglione che lo gestisce. Insieme ai suoi soci e collaboratori, conosce ogni copertina, ogni pagina delle opere che compongono il patrimonio del Centro che oggi è un’istituzione del Comune di Capri.

Creare un archivio che raccogliesse le testimonianze e le esperienze di chi ha apprezzato l’isola, l’ha vissuta, lasciando un segno del suo passaggio. Questo è il sogno di un gruppo di amici che desiderano tutelare l’identità del posto che gli ha dato ospitalità, che li ha visti crescere.

Le sue parole spiegano gli albori di questo progetto: «Il Centro è nato nell’aprile del ’91. Per coincidenza e continuità storica sorge in quella che una volta era la sala di lettura dell’albergo Internazionale. Tra i soci fondatori dell’Associazione Ciccaglione che si occupano del Centro ci sono Enzo di Tucci, vice presidente ed esperto di storia di Capri, Carlo Ferraro e Mario Ferraro. Anche Attilio Lembo e Pasquale Barbato hanno dato lungo il corso della loro vita un prezioso contributo».

Gli occhi di Giuseppe acquistano una tonalità vivace durante l’intervista, le sue mani sfiorano le pagine di un manoscritto posato sul tavolo di legno nella sala. Un punto di approdo e di partenza che ha visto avvicendarsi tanti studiosi presi dalle loro indagini. Le dita disegnano i contorni di quella grafia antica e trasmettono una partecipazione sempre accesa per la sua attività, nonostante i tanti anni di lavoro.

Nel raccontare sottolinea il principio che ha dato l’avvio all’Associazione e dovrebbe animare chiunque abbia a cuore il bagaglio culturale dell’isola: «Il Centro è nato con un intento, pagare con un libro la bellezza che abbiamo ricevuto. Vivendo in questo luogo la pago in impegno civile con i miei compagni che ogni giorno mi affiancano in questa avventura». E ribadisce un altro concetto fondamentale nell’era dei nuovi media, l’accessibilità del sapere. «Questo posto è un’istituzione pubblica e aperta a chi vuole saperne di più. È come la Piazzetta di Capri che si affaccia all’Europa e al mare con l’abbattimento delle carceri nel 1872. Noi lanciamo un invito, ci rivolgiamo soprattutto ai giovani che incarnano il nostro futuro. A tal proposito, nei nostri archivi abbiamo numerose tesi di laurea che rappresentano i nostri semi, che in qualche caso sono germogliati. Realizzare un rapporto di vicinanza e diffusione dei nostri beni ci ha spinto ad aprire una pagina Facebook con la quale proviamo a invitare i giovani ad approfondire. Inoltre, per garantire una buona fruibilità, uno dei nostri obiettivi a breve termine è la digitalizzazione degli archivi».

Ma quali sono queste opere, questi pezzi unici e preziosi più di un gioiello che formano la biblioteca del Centro Documentale? Giuseppe Aprea si alza dalla sedia e comincia a sfiorare i volumi sistemati ordinatamente tra le mensole. Li lambisce con le dita e poi ne prende uno con sicurezza e delicatezza, come se fosse un figlio. «Questo fa parte dei registri di Stato Civile in cui sono contenute le Delibere Decurionali – manoscritti – del Consiglio Comunale di Capri dal 1810 al 1917. Le loro pagine scandiscono con precisione le varie tappe attraverso cui si è snodato il lunghissimo e tortuoso cammino dell’isola verso la sua consacrazione a stella del turismo mondiale. Da questi documenti si capisce che Capri è stata una piazza militare e i militari diventarono fonte di reddito per la popolazione. Ma non è tutto. Dalle dichiarazioni si comprendono i lavori che svolgevano i capresi tra cui l’allevamento dei bachi seta e la pesca del corallo. Gli atti fotografano le sofferenze ma anche la scoperta della bellezza dell’isola da parte dei suoi abitanti. In particolare attraverso gli occhi degli altri il caprese ha capito che ospitando poteva guadagnarsi da vivere».

Le delibere comunali non sono l’unica traccia per ricomporre la storia della vita e lo sviluppo di Capri. Anche i numeri se interpretati nel modo giusto possono raccontare. È lo stesso Aprea a interrogarli e a dargli voce, indossando ora i panni del ricercatore, ora le vesti di archivista. Mostra un piccolo libricino ricavato da un registro di economia del Comune datato 1825 e intitolato ‘O re a Capri… e l’ospitalità divenne mestiere. Il piccolo tomo è frutto delle sue fatiche, «nel libro viene descritta la visita del re Francesco I di Borbone a Capri nel 1825. L’avvenimento è raccontato su basi tecniche, sui provvedimenti messi in atto dall’amministrazione per ricevere il sovrano. Grazie all’elenco delle spese e relative motivazioni ho definito come l’isola si preparò all’evento. Il momento clou? La costruzione di un pontile di legno a Marina Grande che simboleggia una delle prime forme di accoglienza».

Poi è il turno di un’altra meraviglia, il fiore all’occhiello di questo luogo: l’archivio Roberto Ciuni donato dalla moglie Eugenia. Un regalo che rispecchia la stima e la fiducia che il giornalista de Il Mattino nutriva nei confronti del Centro. Giuseppe Aprea ricorda ancora quando lo scrittore bussò alla porta. «Ciuni all’epoca stava scrivendo La Piazzetta e aveva sentito che nel nostro Centro c’era l’emeroteca Eugenio Aprea, un archivio giornalistico insostituibile e unico curato da mio padre. Raccoglie articoli che vanno dal 1947 ai primi anni Sessanta. Tra di noi ci sono state lunghe chiacchierate, scambi di opinioni e idee. Mi raccontò dei suoi esordi giornalistici come giovane cronista di mala in un contesto difficile come quello palermitano. Per noi è stato motivo di grande gioia e orgoglio sapere che l’archivio Ciuni avrebbe fatto parte del Centro Documentale. Il materiale è una raccolta delle sue passioni storiche, si compone di 23 faldoni che contengono appunti, notizie, interviste e documenti diversi relativi al grande lavoro di ricerca storica svolto sull’isola».

Ad arricchire la collezione ci sono anche i capresi. Grazie alle loro passioni hanno messo in salvo pezzi di vita che altrimenti sarebbero andati perduti. Come nel caso dell’archivio fotografico Giuseppe Catuogno, appassionato collezionista di immagini d’epoca. «La famiglia ha donato tutte le istantanee di Giuseppe, che era soprannominato Ciaccariello. Giuseppe aveva raccolto le foto delle famiglie capresi: immagini di matrimonio, da militare, scatti che raccontano momenti importanti. Senza rendersene conto ha salvato ricordi e sentimenti ma anche tradizioni popolari».

In questa sala c’è spazio anche per personaggi meno noti come i coniugi Gargiulo. Lui pittore amatoriale e professore di educazione fisica, lei insegnante di danza. «La signora Gargiulo ha portato l’arte del ballo a Capri. Di cultura inglese, ha creato la prima scuola di danza. Ci ha regalato l’archivio di quadri di Vittorio, suo marito. Cosa custodisce? Paesaggi capresi e altri soggetti. Poi ci ha dato anche del materiale che riguardava la sua scuola di danza».

Quindi non solo fotografie, manoscritti e articoli. Al Centro Documentale di Capri sono stati affidati anche quadri di valore. Uno dei più interessanti e romantici copre la parete all’entrata. L’opera, nata dall’estro di Michele Ogranovitsch, raffigura Marina Grande al tramonto. Chi era l’autore della tela? Un pittore russo sbarcato sull’isola a fine Ottocento, si era innamorato di una fanciulla caprese e l’aveva sposata. La collezione ha avuto inizio con Gelosimana Ogranovitsch, sua figlia e proprietaria dell’albergo Tre Re a Marina Grande. «Questa storia – dice Aprea – ce l’ha raccontata la figlia, e la signora Ogranovitsch ci ha donato il dipinto. La collezione comprende tutti i quadri di questo pittore. Disegnava scene di vita caprese, ci sono una serie di dipinti che abbiamo fatto restaurare e che mostreremo pubblicamente».

Infine, c’è il cosiddetto “archivio dei ricordi”, una serie di interviste realizzate da Giuseppe Aprea ad anziani dell’isola. «Lascio che queste persone raccontino le loro storie, dalla partecipazione alla guerra fino alle conserve di pomodoro fatte in casa. Tutto fa parte di questo tessuto e dobbiamo testimoniarlo».

Questo luogo è veramente uno scrigno di tesori. Dentro ci si trova il passato, il presente e il sentiero per il futuro dell’isola di Capri.

Guardian of the memory

The Document Centre houses a valuable archive. It consists of books, photos, documents and eyewitness accounts of a past that tells the story of Capri

by Marilena D’Ambro | photos by Davide Esposito

It only takes a moment to become entranced by Capri. All you need is a few brief seconds for your gaze to lose itself in the deep blue waters of the Grotta Azzurra, or a minute or two for it to skim over the majestic outline of the Faraglioni on a boat trip. But to fall in love with Capri, and for that intense, deep-rooted feeling to develop, it takes a lifetime, and a deep knowledge of the island. A knowledge that is built up over time, through the island’s history. You need to go beyond the natural beauties dotted around this island with its feminine curves, and to raise the invisible veil that envelops it. Between the walls surrounding the Piazzetta, among the medieval buildings of the old town centre, echo the voices and footsteps of people who have made Capri what it is today. Even the waters lapping the Capri coast bring to light remnants of distant times. The men and women who live in this place carry with them a precious past, and retrace it almost unconsciously as they head towards a present and a future made possible thanks to those who have gone before them. So to love Capri means to set off on a long journey into its memory. But where do you find it? Where can you pick up the threads? At the Island of Capri Document Centre in the heart of Via Le Botteghe. To enter this “house of memories” is to open one of the many doors onto the soul of Capri, the most secret and fascinating of all, because it is composed of a thousand nuances leading in surprising directions. The smell of books tickles the nostrils, and the many books arranged on the shelves talk, eager to tell visitors about an unexplored feature, fact or event involving Capri. There to guide the visitor along the streets of remembrance is Giuseppe Aprea, a local history enthusiast since childhood, Literature and Philosophy graduate and author of numerous books and articles about different aspects of Capri. He welcomes anyone who has a thirst for knowledge with a smile and a wager: that he’ll be able to give them a fragment of the island that is still unknown to them. Giuseppe Aprea is the director of the Document Centre and president of the Achille Ciccaglione Cultural Association that manages it. Together with the association members and collaborators, he knows every cover and every page of the works that comprise the heritage of the Centre, now one of Capri’s local authority institutions. To create an archive that would bring together the eyewitness accounts and experiences of those who have admired and experienced life on the island, leaving a mark of their passage. That was the dream of a group of friends who wanted to preserve the identity of the place that had given them hospitality and seen them grow up. Aprea explains how the project began: “The Centre was set up in April 1991. By coincidence and for the sake of historical continuity, it began life in what was once the reading room of the Internazionale hotel. The founder members of the Ciccaglione Association that looks after the Centre include Enzo di Tucci, the vice president and an expert on Capri history, Carlo Ferraro and Mario Ferraro. Attilio Lembo and Pasquale Barbato have also made a valuable contribution over the course of their lives.” Giuseppe’s eyes light up during the interview, and his hands leaf through the pages of a manuscript lying on the wooden table in the room. The place is a point of arrival and departure that has seen many scholars pass through as they carry out their investigations. His fingers trace the outlines of the old handwriting and transmit his ever enthusiastic participation in the activity, despite the many years of work involved. As he talks, he underlines the principle that led to the setting up of the Association and that should inspire anyone who holds the island’s cultural legacy dear: “The Centre started with one intention: to repay the beauty that we have received with a book. I repay the privilege of living in this place with civic commitment, along with my colleagues who assist me in this adventure every day.” And he stresses another fundamental concept in the era of the new media: access to knowledge. “This place is a public institution and is open to anyone who wants to know more. It’s like the Piazzetta in Capri that looked towards Europe and the sea with the demolition of the jails in 1872. We’re launching an invitation directed especially at young people, who represent our future. In line with this, our archives hold numerous degree theses, representing our seeds that have in some cases germinated. In order to create a close relationship and give our assets a wider reach, we’ve opened a Facebook page to invite young people to explore further. And one of our short-term objectives is to digitalize the archives, to make them more usable.” But what are these works, these unique pieces more precious than jewels that make up the library of the Document Centre? Giuseppe Aprea gets up from his seat and starts skimming through the books neatly arranged on the shelves. His fingers brush lightly along the books and then he picks one out as carefully and delicately as if it were his own child. “This one is part of the Registry Office files containing the Council Resolutions – handwritten – of the Capri town council from 1810 to 1917. The pages provide a precise account of the various stages on the long and tortuous road that the island has taken towards its consecration as a stellar destination for world tourism. From these documents it is clear that Capri used to be a military stronghold and the soldiers provided a source of income for the population. But not only that. The declarations also reveal the type of work the inhabitants of Capri were engaged in, including silkworm farming and coral fishing. The documents capture the sufferings of the islanders, but also their discovery of the beauty of the island. In particular, through the eyes of others, the Capri inhabitants realised that they could earn a living through hospitality. The council resolutions are not the only path to reconstructing the history of the life and development of Capri. Numbers also help to tell the story, if they are interpreted correctly. Aprea himself examines them and gives them a voice, sometimes playing the role of researcher and sometimes that of archivist. He shows us a small book that draws on the council accounts register dated 1825, titled ‘O re a Capri… e l’ospitalità divenne mestiere. (“The King comes to Capri…and hospitality becomes a business”). This small volume is the fruit of his own labours: “The book describes the visit by King Francis I of Bourbon to Capri in 1825. The event is narrated starting from a technical basis: the measures undertaken by the administration to prepare for the sovereign’s visit. Using this list of expenses and the reasons given for them, I worked out how the island prepared for the event. And the highlight? The construction of a wooden landing stage at Marina Grande, symbolizing one of the first manifestations of the hospitality industry.” Then we turn to another marvel and the crowning glory of this place: the Roberto Ciuni archive donated by his wife, Eugenia. It is a gift that reflects the esteem and trust in which Ciuni, a journalist for Il Mattino, held the Centre. Giuseppe Aprea still remembers when the writer knocked at the door. “At that time, Ciuni was writing La Piazzetta and he had heard that our Centre housed the Eugenio Aprea library of newspapers and periodicals, an irreplaceable and unique journalist archive curated by my father. It contained articles from 1947 to the early 1960s. We had long conversations together, exchanging opinions and ideas. He told me about his early years as a journalist, working as a young crime reporter in the very difficult situation that existed in Palermo at the time. It was a source of great joy and pride when we found out that the Ciuni archive was to become part of the Document Centre. The material is a collection of all the subjects he was passionate about, consisting of 23 folders of notes, news, interviews and various documents regarding the extensive historical research he carried out on the island.” The inhabitants of Capri have further enriched the collection. Thanks to their enthusiasm, pieces of Capri life have been saved that would otherwise have been lost. As in the case of the photographic archive of Giuseppe Catuogno, an enthusiastic collector of historical images. “The family donated all the snapshots that belonged to Giuseppe, nicknamed Ciaccariello. Giuseppe had collected photos of Capri families: wedding photos, photos of military service, snaps capturing important moments. Without realising it, he had saved memories and emotions, but also the people’s traditions.” In this room there’s space for less well-known people, too, such as Mr. and Mrs. Gargiulo. He was an amateur artist and PE teacher and she was a dance teacher: “Mrs. Gargiulo brought the art of dance to Capri. She came from an English background, and she created the first school of dance on the island. She gave us her husband Vittorio’s archive of paintings. What is in it? Paintings of Capri landscapes and other subjects. And she also gave us material about her dance school.” So it isn’t just photographs, manuscripts and articles. Some fine paintings have also been entrusted to the Capri Document Centre. One of the most interesting and romantic of these paintings covers the walls of the entrance hall. It is by Michele Ogranovitsch, and depicts Marina Grande at sunset. So who was the creator of the painting? He was a Russian artist who arrived on Capri in the late 19th century and fell in love with a Capri girl and married her. The collection was started by Gelosimana Ogranovitsch, his daughter and the owner of the Tre Re hotel at Marina Grande. “His daughter told us the story and his wife donated the painting,” says Aprea. “The collection includes all the artist’s paintings. He painted scenes of Capri life; we’ve had a series of paintings restored, and we’re going to exhibit them to the public.” Finally, there’s the so-called “archive of memories”, a series of interviews conducted by Giuseppe Aprea with old people on the island. “I let these people tell their stories, from what they did in the war to their home-made tomato purée. Everything is part of the fabric and we need to bear witness to it.” This place is a real treasure chest. Within it you can find the past, the present, and the future path for the island of Capri.

Torna a sommario di Capri review | 37