La seduzione di un’isola

La seduzione di un’isola

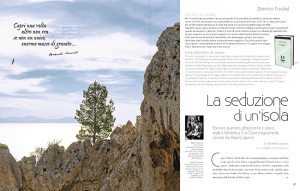

Donna e guerriero, affascinante e aspra, reale e fantastica. È la Capri magicamente narrata da Alberto Savinio

di Daniela Liguori | foto di Raffaele Lello Mastroianni

Capri è “donna” solo lì dove «la terrazza pompeiana», anticamera dell’isola, si erge «gentile, aerea, fiorita» e «grappoli pesanti di limoni dorati» e «verdi vigneti» «dichinano a scale verso la marina». Altrove e, soprattutto, «nella inviolabile cinta che la circonda», essa rivela «il suo carattere rude, maschio, guerriero». Così scrive Andrea De Chirico, in arte Alberto Savinio, in quella vivida descrizione dell’isola che è il libro Capri.

Partecipe del clima dissacrante delle avanguardie storiche del primo Novecento e, al tempo stesso, imbevuto di quella tradizione mitico-letteraria che respirò sin da bambino nella sua città natale, Atene, Savinio è noto per l’eclettismo e per l’“energia creativa” della sua opera. Fu, infatti, scrittore, pittore, musicista, drammaturgo. Amante della “vita randagia”, come affermò egli stesso e come testimonia il suo «fedele valigiotto costellato di tante etichette di alberghi», Savinio giunse a Capri nella primavera del 1926, pochi mesi dopo il matrimonio con l’attrice Maria Morino, incontrata al Teatro d’Arte di Roma diretto da Pirandello. Qui strinse una profonda amicizia con Curzio Malaparte che, nel 1941, gli commissionò la decorazione per le maioliche del pavimento dello studio della sua villa a Capri. Il motivo della lira, suggerito dallo stesso Malaparte, è ripreso dallo schizzo di Goethe che figura sul manoscritto del Viaggio in Italia.

L’isola gli apparve seducente e aspra per la “doppiezza” del paesaggio che coniuga una natura coltivata – i terrazzamenti scavati nelle montagne, gli eleganti loggiati, i tappeti erbosi – e una natura selvaggia e incontaminata, che esplode improvvisa nell’irregolarità di dirupi scoscesi e orribili precipizi. Capri diviene così una “donna” le cui forme sinuose adombrano il suo vero volto di «isola di ferro»: è giacimento delle «rocce più spaventose che natura abbia mai colato nei suoi crogioli mostruosi» senza disgiungere orrore e fascinazione. Non è tuttavia soltanto il paesaggio a catturare lo sguardo di Savinio. Attraverso colori e immagini che gareggiano «con quelli dell’isola» – sottolinea Raffaele La Capria – “l’immaginifico viatore” ci accompagna in un «viaggio reale e fantastico», restituendone insieme la quotidianità e la “numinosità”. Non diversamente da altre sue opere – quali Ascolto il tuo cuore, città e La casa ispirata, dedicate rispettivamente a Milano e Parigi – Capri ci restituisce, infatti, un’isola reale e fantasmatica, popolata di “gente peschereccia” e albergatori, pittori e turisti, ma anche di spiriti e presenze sinistre. Un’isola, dunque, dove i confini tra reale e immaginario si lacerano e il perturbante irrompe improvviso facendo apparire i Faraglioni come “cattedrali gotiche” o la Grotta Azzurra come una “volta vastissima” fatta da «innumerevoli occhi azzurri».

Per raccontare l’esperienza vissuta a Capri, lo scrittore tratteggia sia la vita «silenziosa ed elementare degli autoctoni», della “gente peschereccia”, sia «quella truculenta, tra frivola ed estetizzante, di tutti gli ulissidi che, attratti dal non mai spento canto delle Sirene, convergono qui dai punti più remoti del globo»; descrive sia i porti, dove le barche «dormono sulla fiducia delle ancore» o, «coricate sulla riva», «riposano sul fianco come foche che allattano i loro piccini», sia i «vestiboli eccitanti degli alberghi» e le «botteghe civettuole» disseminati sull’isola ad uso turistico. Ma il vero volto dell’isola è per lui quello aspro e orrido di Anacapri, dove le strade «sul più bello ti abbandonano, poi magari riprendono più in là, intermittenti, a scatti» o sono soltanto «sassi disposti in fila e che talvolta precipitano in una brusca discesa» e dove mare e vento, che hanno “ammorbidito” quel che era «un unico, enorme masso di granito» scolpendone con il tempo le forme, lasciano ancora udire la loro forza violenta: il mare «a ogni svolto della strada a gomiti, più profondo abbaia e schiuma» mentre «più sinistro ulula il vento nei pini disperatamente aggrappati ai fianchi del Solaro». «Eccomi condannato a camminare a tastoni su per la più paurosa e stregonesca strada del mondo – racconta Savinio – sospeso come un vecchio uccellaccio da tempesta tra cielo e mare». In questi luoghi il «paio d’occhi trasfiguratori» posseduti da Savinio che, come scrive Vincenzo Trione, gli «consentono di percepire l’odor dei», colgono la presenza nell’isola del suo più antico passato. Qui un cane incontrato per caso si tramuta in una guida misteriosa, pronta a condurlo sulla cima del Castiglione, tra «i ruderi del castello imperiale», «per i cortili deserti, per gli squallidi corridoi sparsi di alti tappeti erbosi, sotto le volte dei soffitti rotti a metà, davanti a orribili finestre aperte sul buio». Esplorando, infine, il Castello e la Torre che sovrastano la punta orientale di Capri – ossia i «luoghi in cui più viva si perpetua la memoria di Claudio Tiberio Nerone» – la vista delle rupi scoscese e dei precipizi a picco sul mare quali il Salto di Tiberio si fa esperienza della seduzione provocata dal baratro. «Quanto tempo rimasi chino sul Salto di Tiberio? Non saprei. Allora solamente mi avvidi del mio incantamento, quando chiara mi divenne pure la cagione che lo aveva provocato. […] Dal fondo di quel baratro ove ogni sentimento di distanza era scomparso, sentivo salire una interrogazione dolcissima, insistente. Nel vuoto che rasentava la rupe, la Morte cantava con accenti inimitabili». Seduzione che evoca gli spettri di coloro che hanno tentato invano di violare la cima dell’Arco Naturale e il fantasma dello stesso Tiberio e che lascia echeggiare ancora la voce della dea della storia Clio.

Sui passi di Savinio

Per chi ama l’isola questo libro è un piccolo gioiello. Una meraviglia di sensibilità, umorismo, cultura. Scritto nel 1926, alcuni brani erano stati pubblicati su La Nazione di Firenze fra il ’33 e il ’34 poi più niente fino al ritrovamento del testo tra le carte dell’autore e la successiva pubblicazione nel 1988. Seguendo i passi, spesso fantastici, di Alberto Savinio ci si ritrova immersi nell’incanto di Capri sin dall’inizio quando ancora non si è sbarcati e l’isola è lì, terra di roccia in mezzo al mare che calamita gli sguardi di tutti, Savinio compreso, «punto io pure lo sguardo sui contorni indeterminati dell’isola solitaria, sulle cime dei suoi monti levati nel morbido cielo del meriggio aprilano. Una bianca, dolcissima nube fa anello intorno la vetta del monte maggiore». Una volta a terra è tutta una scoperta e una pennellata di colore che riviviamo attraverso le 72 pagine di un viaggio, reale e fantastico, dove Capri non è solo azzurra. | In the footsteps of Savinio.This book is a real gem for anyone who loves Capri. A marvel of sensitivity, humour and culture. Written in 1926, some extracts were published in the Florence newspaper La Nazione between 1933 and ’34, then nothing more until the text was discovered among the author’s papers and published in 1988. Following in the often highly imaginative footsteps of Alberto Savinio, we find ourselves immersed in the magic of Capri right from the start, before we have even landed, when the island is there, a rocky piece of land in the middle of the sea that draws the gaze of all like a magnet, including Savinio: “I focus my gaze on the vague outlines of the solitary island, on the peaks of its mountains rising up into the soft April midday sky. The gentlest of white clouds forms a ring around the peak of the highest mountain.” Once on land, everything lay ready to be discovered and described in vivid colours, taking us through 72 pages of a journey, real and imaginary, where Capri is more than just the azure isle.

An island of seduction

Woman and warrior, fascinating and fierce, real and imaginary. That’s the Capri magically narrated by Alberto Savinio

by Daniela Liguori | photos by Raffaele Lello Mastroianni

Capri is “female” only there, where the hillside climbs up like a sort of Pompeian terrace-style antechamber to the island, “graceful, airy and flower-filled”, where “branches laden with golden lemons” and “green vineyards… slope down in stepped terraces towards the sea”. Elsewhere, and above all “inside the unbreachable girdle that encircles her”, the island reveals “her rough, masculine, warrior-like nature”. So writes Andrea De Chirico, better known under his professional name Alberto Savinio, in the vivid description of the island presented by his book Capri.

Having been a part of the convention-defying climate of the historic early 19th century avant-garde, while at the same time imbued with the mythical-literary tradition that he had breathed in since his childhood in Athens, the city of his birth, Savinio is renowned for the eclecticism and “creative energy” of his work. Indeed, he was not only a writer, but a painter, musician and playwright, too. A lover of the “wandering life”, as he himself affirmed, testified by his “faithful suitcase, plastered all over with hotel labels”, Savinio arrived on Capri in the spring of 1926, just a few months after his marriage to Maria Morino, whom he had met at the Teatro d’Arte in Rome, directed by Pirandello. On Capri,he formed a close friendship with Curzio Malaparte who, in 1941, commissioned him to design the decorative majolica floor tiles in the study of his villa on Capri. The lyre motif, suggested by Malaparte himself, is taken from the sketch by Goethe that appears on the manuscript of his Italian Journey. To Savinio, the island appeared both seductive and fierce because of the “duality” of the landscape, combining ‘cultivated nature’ – terraces carved from the mountains, elegant porticos and grassy lawns – with the wild, unspoilt nature that explodes suddenly in the irregularity of the rocky cliffs and the terrifying precipices. So Capri becomes a “woman” whose sinuous curves conceal the true face of the “iron island”, deposit of the “most fearful rocks that nature has ever cast in its monstrous melting pot”, without separating horror and fascination. But it is not just the landscape that captures Savinio’s gaze.

Through colours and images that compete “with those of the island,” as Raffaele La Capria points out, “the imaginative wayfarer” accompanies us on a journey that is both “real and imaginary”, bringing out both its everyday character and its mystical quality. Like his other works, such as I Listen to Your Heart, City and “The Inspired Home”, dedicated to Milan and Paris respectively, Capri evokes for us a real and imaginary island, populated by “fishing folk” and hotel owners, painters and tourists, but also by spirits and ghostly presences. So an island where the boundaries between the real and the imaginary are torn down, and where disturbing elements suddenly burst in, making the Faraglioni appear like “Gothic cathedrals” or the Grotta Azzurra like a “cavernous vault” made up of “innumerable blue eyes”. To describe his experiences on Capri, the writer sketches both the “silent, simple life of the natives”, the “fishing folk”, and that “gruesome life, between frivolity and aesthetic aspirations, of all those modern-day Ulysses who, drawn by the undying call of the Sirens, converge on the island from the farthest corners of the globe”. He describes the harbours, where the boats “sleep, resting on their trust in the anchors” or “lie on their sides on the shore, like seals feeding their young”, as well as the “bustling hotel lobbies” and “coquettish boutiques” scattered around the island for the benefit of the tourists. But the true face of the island for Savinio is the harsh, terrible face of Anacapri, where the streets “abandon you without warning, perhaps to reappear again a bit further on, intermittently, in fits and starts” or are simply “stones arranged in a row, sometimes plunging abruptly downwards”; where the sea and the wind that have softened what was “a single, enormous block of granite”, carving shapes from it over time, still let their violent force be heard: the sea “rages and froths more powerfully at every hairpin bend in the road”, while “the wailing of the wind in the pines clinging desperately to the sides of Mount Solaro becomes ever more sinister”. “Here I am, condemned to grope my way along the most terrifying, bewitched road in the world,” writes Savinio, “suspended like an old storm bird between the sky and the sea.” In these places Savinio’s “transfiguring eyes”, which, as Vincenzo Trione writes, “enable him to scent the odour of the gods”, capture the continuing presence on the island of its most ancient past. Here, a dog, encountered by chance, turns into a mysterious guide ready to lead him to the top of the Castiglione, among “the ruins of the imperial castle”, “through deserted courtyards, along squalid corridors covered here and there with clumps of tall grass, beneath semi-ruined vaulted roofs, in front of fearful windows opening onto darkness.” Finally, exploring the Castello and the Torre that stand at the easternmost point of Capri – in other words “the places where the memory of Tiberius Claudius Nero is most vividly perpetuated” – the sight of the rocky crags and steep cliffs high above the sea, such as the Salto di Tiberio, makes one feel the seduction of that sheer drop. “How long did I remain crouched over the Salto di Tiberio? I couldn’t say. I only realised the spell I had been under when the cause of it became clear to me. […] From the bottom of that sheer drop, where all sense of distance had disappeared, I heard a sweet, insistent questioning rise up. In the void that skirts the rock, Death was singing with its inimitable tones.” It is a seduction evoking the spectres of those who have tried in vain to trespass upon the peak of the Arco Naturale, and the ghost of Tiberius himself, a seduction that lets the voice of the goddess from the story of Clio continue to echo.

Torna a sommario di Capri review | 38